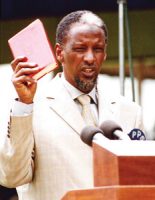

In appointing Khalif Minister for Labour and Manpower Development in 2003, Kibaki had brought to his government one of the most iconic leaders of the Second Liberation movement from northern Kenya — a region not associated at the time with mainstream opposition politics.

The pride of Wajir, he became the first Cabinet minister from the county and only the second from the North Eastern region after Hussein Maalim Mohammed from neighbouring Garissa County.

A journalist who had worked with the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) before joining politics, Khalif came from a long line of leaders, most of them of a stubborn streak.

His father was one of the first African inspectors of police in Kenya and later a chief while his eldest brother, Abdirashid Khalif, had been to the Lancaster independence talks, as a special representative of the Northern Frontier District (NFD).

And while the talks, held in February 1962, were largely a duel that pitted KANU against the Kenya African Democratic Union (KADU) on a new constitutional framework, Abdirashid took the conference by surprise when he said he was for neither of the two dominant parties.

He argued that NFD should secede and be united with the Republic of Somalia because the region had always been isolated and marginalised. Laws passed between 1902 and 1934 restricted movement of persons entering or leaving the six districts of Isiolo, Garissa, Mandera, Marsabit, Moyale and Wajir.

While an ensuing referendum on the matter won when five out of the six districts (80% of the population) voted to secede, the British administration did not approve the results.

This led to what was termed the Shifta War, a secessionist conflict in which ethnic Somalis from NFD sought to secede from Kenya and join Somalia.

Khalif’s other brother, Abdisitar Khalif, whose mantle he took in the family leadership, had been an MP since independence — on and off — becoming a major thorn in the side of Mzee Jomo Kenyatta.

Having aligned himself with Jaramogi Oginga Odinga in his ideological turf war with Mzee Kenyatta, Abdisitar fled to Somalia following the crackdown on the Kenya People’s Union (KPU) of which he was a leading light.

Prevailed upon to return to Kenya and join KANU to contest during the 1969 General Election after Mzee Kenyatta forgave him, Abdisitar agreed. He won the election and was appointed Assistant Minister for Finance. But he quickly fell back to his rebellious ways, forgetting the principle of collective responsibility by which ministers are traditionally expected to abide. He told the country that as an Assistant Minister for Finance he knew the President’s salary and he felt that it was too much, given the country’s poverty level.

For his audacious remarks, he was moved from the Finance docket to the less influential Housing and Social Services docket. But he continued to rabble-rouse, rubbing the Attorney General (AG) Charles Njonjo the wrong way. The AG warned him to stop his attacks on the government or face arrest.

Soon Abdisitar was arrested in Mombasa and jailed for one year, thereby losing his seat. He rejoined Jaramogi on his release, but could not run for the elections under a proscribed party.

It was to this chequered heritage that Ahmed Khalif arrived on the political scene in 1979, aged 29, having been prevailed upon by elders to step into the place of his brother who had been expelled from KANU.

Khalif was re-elected in 1983 and was soon embroiled in the heated politics following the Wagalla Massacre. One of the lowest moments in independent Kenya’s history, the carnage started when on 10 February 1984, members of the Degodia clan of the Somali were gathered by security forces, held at the Wajir Airstrip and hordes of them killed under the guise of a security operation to weed out bandits.

Khalif, a member of the Degodia clan and the local MP, became the face of the outcry, telling Parliament the following week that more than 1,000 people starved to death following the inhuman conditions under which they were held at the airstrip.

He was again the face of the resistance against the so-called Red Cards, special identification documents which Kenyan Somalis were required to carry to distinguish them from those of Ethiopia and Somalia. Khalif opposed it as unconstitutional and hired lawyer Mohammed Ibrahim, now Supreme Court Judge. He won the case and became a hero among his constituents and the Somali community.

As expected, he joined other opposition stalwarts ahead of the first multiparty elections in 1992. But feeling threatened by the onslaught from the likes of Kenneth Matiba, Oginga and Kibaki, President Moi pleaded with Degodia elders to prevail upon Khalif to return to KANU.

Hassan Ndzovu in his 2014 book, Muslims in Kenyan Politics, also suggests another reason for Khalif’s failure to join the Forum for the Restoration of Democracy (FORD) despite his push for the re-introduction of political pluralism. He argues that when FORD leaders sought to recruit Khalif as its representative for the North Eastern Province, he declined the offer because he did not want to embarrass his colleagues in the Supreme Council of Kenya Muslims (Supkem) who had positions in the Moi government.

Thus Khalif, the erstwhile harsh government critic, ran on a KANU ticket in 1992 and was appointed Assistant Minister for Finance on winning the election. In 1997 he was defeated by Weliye Adan Keynan of Safina but would bounce back in 2002.

Ahead of the historic elections Khalif had, from 2000, become an active member of the Ufungamano Initiative that was pushing for the constitutional reforms amid strong resistance from the Moi government.

He rode on this campaign and on memories of his defence of the community during the Wagalla Massacre and subsequent clamour for Somalis to carry special identity cards to win the seat despite running on as a NARC candidate, a new and fringe party (at least in his region).

After his win, Khalif was appointed Minister, the only one from the North Eastern Province. This ultimate admission to the centre of government after decades of struggle in the peripheries were cut short when he died in a plane crash that also killed two pilots in Busia on 24 January 2003.

Three other ministers — Martha Karua, Raphael Tuju and Jebii Kilimo — were injured when their chartered aircraft hit power lines and crashed into a residential estate shortly after take-off.

Other ministers and senior officials who had been on the plane from Nairobi had decided to spend the night in Busia rather than take the return flight on the ill-fated aircraft.

Officials said the 24-seater Gulfstream failed to gain sufficient height because the airstrip had a short runway, forcing it to hit two houses and a power line.

The officials were visiting Busia — the home of then Home Affairs Minister Moody Awori — as part of the celebrations for the NARC election victory.

Khalif died shortly after reaching hospital, having been minister for barely 20 days, becoming the shortest-serving minister, not just in the Kibaki Cabinet, but perhaps in Kenya’s history.

Khalif’s Assistant Minister was Peter Odoyo, then MP for Nyakach in Nyanza region and a former economist at the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the US Agency for International Development (USAID).

Khalif’s death dampened the mood of great optimism that was reigning in Kenya since NARC’s victory, three weeks earlier, which had swept away KANU, the independence party responsible for years of economic stagnation and political oppression.

The death also came at a fragile time for the Kibaki government whose leader was frail following a car accident ahead of the elections. His Vice President, Kijana Wamalwa, had also just returned from London where he had been hospitalised for an illness that would later that year take his life.

In 2009 the High Court sitting in Nairobi declined to compensate Khalif’s family on grounds that they were time-barred in seeking compensation for his death. During the case, Khalif’s son, Mohammed, and wife Fatuma Garore, had sued Africa Commuter Services and MIA International Ltd for allegedly causing the death of the minister through negligence.

The Busia incident cut short the career of a Cabinet minister who was the senior-most politician from Wajir at a time when those from the Ogaden clan in Garissa dominated the politics of the region.

In the ensuing by-election, Khalif was succeeded by his 23-year-old son Mohammed Khalif who became Assistant Minister.

Born in 1950 in Wajir, Khalif — one of the few trained journalists to have come from North Eastern Province — attended Wajir Government School for his primary education. He later went to Wajir Secondary and Nairobi High schools before joining the University of Nairobi for a Journalism course.

He thereafter had a career in the civil service as an information officer before joining BBC from where he joined politics.

Perhaps his training and practice as a journalist shaped his politics, sharpening him as a crusader against oppression. Khalif was always in the forefront of defending Muslims, especially against Garissa politicians whom he believed were misleading Moi on the state of security in the region. The so-called Somali Probe Committee had called for a much wider screening of Somalis in which the Immigration Department held little sway.

Believing this ‘Red Card’ policy to be the Kenyan version of the Jim Crow laws that enforced racial segregation in the southern United States, Khalif wrote a letter to Moi stating that that some politicians from North Eastern had for a long time called for screening of the people of the region in order to harass other members of the community on account of tribal, political and business considerations.

Khalif maintained that the culprits in the matter of poaching and banditry were members of the business community mainly based in Nairobi and especially those engaged in the transport industry.

For this, some Kenyan Somali MPs attacked Khalif, accusing him and other protesters of sympathising with aliens. He was soon hounded out of Supkem and was threatened with expulsion from KANU.

Yet unlike his brother who had fought for the secession of the NFD the veteran politician was eager to demonstrate that Muslims were as Kenyan as anyone else.

For instance, following the 1998 bombing of the US embassies in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam, Khalif led the region and Muslims in condemning the terrorist act.

“We believe that no Kenyan Muslim was involved is such a dastardly act. We know that there is political tension in the country and Muslims have been oppressed for decades. But that does not justify killing, maiming and destruction of property,” Khalif said in an interview.

That statement set the mood for other Muslims to come out and be seen as part of the concerned citizens at a time when the anti-Muslim sentiments were on the rise because to the actions of Osama Bin Laden, the founder of the pan-Islamic militant organisation al-Qaeda.

Despite his disagreements with other Muslim leaders, the physical fitness enthusiast was to his last days dedicated to Supkem of which he was once Secretary General.

We will never know how Khalif, the former journalist, would have performed in his docket that requires hard-nosed managers to deal with unending demands from trade unionists, but in retrospect it appears a plateful awaited him.

While he was in the office for only three weeks, Khalif had taken over the ministry at a time when there were calls for reforms of archaic labour laws.

Moi had kept a tight leash on the labour movements with trade union officials routinely arrested for agitating for workers’ rights and it fell on the Kibaki government that swept to power on a reform agenda, to change things for the better.

It was also a time when the International Labour Organisation (ILO) had launched a programme to eradicate child labour in the world, especially in the agriculture, construction, cross-border trade, domestic service, fishing, hotel and tourism, as well as quarrying and mining sectors.

Kenya had participated in an ILO regional programme that sought to withdraw, rehabilitate, and prevent children from engaging in hazardous work in the commercial agriculture sector in East Africa.

Kenya was with other African countries in the campaign for adoption of uniform labour laws within the New Partnership for African Development (Nepad) to enable them to collectively tackle serious problems facing the continent such as runaway unemployment, poverty as well as HIV/AIDS.

All this fell on Khalif’s successor Newton Kulundu, the MP for Lurambi, who served as Labour Minister from 2003 to 2007.

A conversation with the late Minister’s constituents, as well as other leaders who knew Khalif, revealed a man of moral courage who was dedicated to the expansion of Kenya’s democratic space.

“He was a towering figure, both physically and metaphorically, pristine in behaviour and values,” said journalist and socio-political commentator Hassan Diriye, from the neighbouring Wajir South Constituency.

Diriye described Khalif as a cut above his contemporaries; a principled man at a time leaders from the region kowtowed to the powers that be to get favours.

Be that as it may, there is no knowing which side Khalif would have taken in the upheaval that soon engulfed the NARC government after some members of the Cabinet alleged they had been short-changed in the sharing of government positions.

But one thing is for sure: in appointing the 53-year-old Ahmed Khalif to the Cabinet, President Kibaki had picked a principled man and a reformist leader who came to his court highly recommended.