Having been a long serving and successful Finance and Planning Minister, two of the Es — economy and empowerment — wouldn’t be unfamiliar territory for him. He needed to entrust the third E, education, to a veteran. And that fell on no less than George Musengi Saitoti.

During his 2002 Presidential campaign Kibaki had promised Kenyans free primary education, a proposition his political nemesis laughed off. Once he became President, he needed to prove them wrong. The taskmaster who Kibaki entrusted to deliver this promise was Saitoti, a former University of Nairobi professor.

Kibaki’s campaign had pledged to deliver free and compulsory primary education within the first 100 days of his Presidency. The pledge sounded easy on paper until you were hit by the reality on the ground. The classrooms were not enough to accommodate the numbers expected, teachers were too few for the envisaged huge number of learners and there was a lack of resources in the public coffers to facilitate the same.

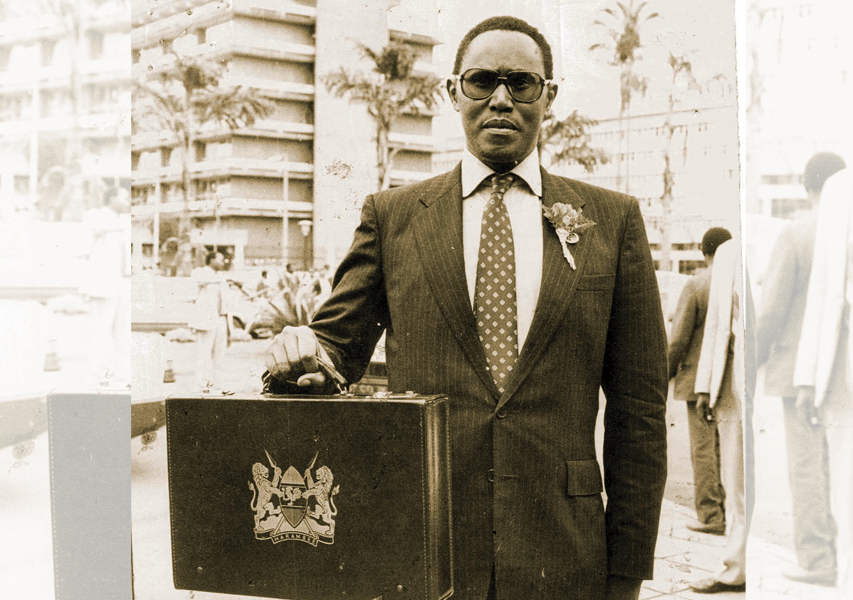

However, President Kibaki was determined. And Saitoti was the man to see it happen. In Saitoti, it wasn’t just faith in his ability to perform, but perhaps also a shared background. They were both practising Catholics and alumni of Mangu High School. While Kibaki branched into economics, Saitoti studied mathematics. Both would later serve as ministers for Finance and Planning, and also vice presidents under President Daniel arap Moi, with Kibaki preceding Saitoti.

So far there is an unshared story about the two men. Just before the National Rainbow Coalition (NARC) and Kibaki came to power, the two gentlemen had made a secret pact to support the other to the hilt, when and if NARC won the election. There was a background to that. NARC was a union between the National Alliance Party of Kenya (NAK) to which Kibaki belonged and had already been picked as the presidential candidate. The other partner was the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) where Saitoti was the senior-most front-runner in the presidential race having, like Kibaki, been a long-serving Vice President.

According to politician Joseph Kamotho, an insider in the power-sharing negotiations preceding the 2002 elections, during the final stages of the negotiations at a meeting held at the home of politician Moody Awori (later appointed Vice President), Kibaki and Saitoti met privately to agree on which of the two would be the NARC presidential candidate. Saitoti stepped aside for Kibaki and pledged his full support towards making Kibaki’s Presidency a success. For Kibaki, compulsory free primary education and later secondary education wasn’t a sudden, impulsive 2002 campaign pledge. It is what he had always believed in ever since he was main architect in writing of the 1963 pre-independence Kenya African National Union (KANU) manifesto that helped the party win elections and form the first independence government. In the manifesto, team Kibaki was resolute about the direction education should take in independent Kenya.

The manifesto read in part:

“In the past it has been the policy to educate a relatively small number of children on the grounds that the country doesn’t possess the money to build the schools necessary to accommodate all the children. We firmly believe that it is better to educate all the children in huts than to waste huge sums on expensive buildings only to cater for a part of our children… KANU is strongly opposed to the practice of eliminating students by process of examinations… Not only is this unfair to a section of our children but it brings with it numerous social problems as well as risk to security and stability. KANU believes all children should access primary education and thereafter secondary education… But for those who attain primary education and cannot go further for any reason, they should be compulsorily required to attend a technical or vocational school for two years. Such a programme would, in addition to mitigating other factors, would accelerate the pace of our efforts to create a pool of skilled and semi-skilled labour…The children of Kenya must be taught to build their motherland and to love her rather than be allowed to develop a slavish mentality under a stilted education system inherited from the colonialists…”

Thus, for President Kibaki, compulsory free primary education wouldn’t be a trial-and-error project. It would be central pillar of his transformational agenda. Within days of taking power, there was an executive order that all eligible primary school children report to the nearest public school. It didn’t matter there were not enough classrooms, desks or teachers. First report to school and leave the rest to us was the government directive, and which the provincial administration had instructions to implement to the letter.

It worked. The children reported to school. With time, the classrooms came, so did desks, and teachers. In the first place, the government allocated more resources to education from whatever meagre resources were available at the Exchequer. Then as the government sealed loopholes in tax collection; reined in tax evaders; and made it increasingly difficult for looters to steal tax-payers money, more budgetary allocation was available for the education kitty. In the meantime, Kenya’s development partners realised indeed it could be done, and chipped in as well.

At the end, Kenya’s free primary education model gained traction and world acclaim. A most celebrated success story on the experiment came from Eldoret where 84-year-old Kimani Maruge decided to go to school. His story became an international cause célèbre, and formed the basis of a Hollywood movie! And on his retirement, US President Bill Clinton when asked which man or woman he thought of as hero, he named Kenya’s President Mwai Kibaki on the account of making possible universal free and compulsory basic education in his country.

At the operational level, Kibaki must have been proud that it was Saitoti he’d entrusted to implement his flagship project.

Kibaki’s second term began on sad and regrettable note. Results of presidential poll of December 2007 had been disputed leading to widespread violence, deaths and destruction of property well into the early days of 2008. So, the first priority in his second term was to restore peace, law and order. It is regrettable that just one month of violence would claw back on most of the economic gains and prosperity of the first five years of Kibaki administration.

As part of the national healing and reconciliation, when naming his second term inaugural cabinet, President Kibaki left half of the vacancies unfilled, itself a signal that he was ready to accommodate his rivals in a government of national unity.

In the new line-up, Saitoti was named Minister for Internal Security. Once again, the President demonstrated the great faith he had in the mathematics professor.

There were indeed trying times, as the post-election violence threatened to obliterate not just the achievements of Kibaki’s first term, but literally the very fabric of the Kenyan nation as it existed. It is Saitoti Kenyans — and indeed the whole world — were looking to help the President restore sanity in the country, previously regarded as oasis of peace in a troubled region. The future looked bleak.

Once more, Saitoti didn’t disappoint. Peace and tranquillity eventually returned to the country, a situation that allowed the mediation talks to take place with former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan as chief mediator of the negotiations team that included former Tanzania President Benjamin Mkapa and former South Africa First lady, Graca Machel.

Heading the Internal Security docket in the prevailing circumstances of the day was no walk in the park. First, it required the trust of all parties involved. In that, it helped that Saitoti had previously, and at different times, worked closely with the various parties in the post-election conflict.

Secondly, Kibaki’s new Minister for Internal Security had won the trust of the international community over the years. In 1990–1991, Saitoti had worked as chair of the joint board of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund on Africa, while in the 1999-2000 period he served as President of the Africa, Caribbean, and Pacific/European Union (ACP/EU) group that negotiated the Lomé III development partnership agreement. In the Kenya post-election peace mediation, it also counted for something that Saitoti was a personal friend of the lead negotiator, Annan, which helped open many a door when the mediation process appeared headed for the rocks.

Eventually, the talks bore fruit.

In the Government of National Unity formed after signing the peace pact, Saitoti was retained in the Internal Security docket to the satisfaction of all parties.

In the new dispensation, he found himself with an added — and delicate — responsibility. He would be the chair of the inter-ministerial committee handling the matter of the Kenyan cases at the International Criminal Court (ICC) at The Hague in the Netherlands. It was no easy task given the high emotions attendant to the ICC matter.

Meanwhile, Saitoti also found himself with extra duties as the acting Minister for Foreign Affairs after then minister, Moses Wetangula, was requested to step down pending investigations on corruption allegations. Saitoti took it all in his stride.

Then sprang up yet another major security challenge: The terrorist grouping Al-Shabaab and their backers, the Al-Qaeda, who, so far, had made sporadic attacks on Kenyan soil. In time, these attacks became so bold that they began to appear, for all intents and purposes, like a declaration of war on Kenya. The terrorists would strike in bold daylight to kill or take hostage Kenyans and/or foreign nationals visiting the country.

Something had to be done and urgently so. The National Security Committee chaired by President Kibaki mandated Saitoti and his Defence counterpart, Mohamed Yusuf Haji, to devise a solution to the Al-Shabaab. They recommended that — for the first time in the country’s history —o a full-scale war outside Kenya’s boundaries. Before that, Kenyan troops had only been to combat zones outside the country as part of the UN peace-keeping missions.

Yet another indicator that Kibaki had trust in Saitoti to handle delicate assignments in his administration is that it was Saitoti not his defence counterpart or the military generals who in 2011, made the formal announcement that Kenya was going to war on Somali soil.

The incursion into Somali was adjudged a great success when Kenyan troops single-handedly stormed the terrorists’ hotbed of Kismayu, and started dismantling the otherwise seemingly formidable Al-Shabaab. Over time, the hitherto chest-thumping ragtag force, has progressively been reduced to a disjointed grouping of motley bandits.

Before he died in a helicopter crash in June 2012, Saitoti had embarked on yet another delicate mission: taking head on the drug cartels and kingpins in the country. Actually, it is through the process he initiated that Kenya upped the war on drug barons to a point of extraditions and long jail sentences for notorious Kenya-based drug barons who for years had evaded justice either by corrupting or bullying the bureaucracy.

The day before he died, Saitoti gave a keynote address at a high-level government seminar attended by Kibaki at a coast hotel. The Minister passionately warned politicians against allowing their selfish ambitions to threaten peace and stability ahead of the 2013 General Election. Late in the evening of the same day Saitoti returned to Nairobi so he could leave early the next morning to Siaya County. He never arrived.

In both dockets —Education and Internal Security —Saitoti was fortunate to work with professionals and like-minded people as his assistant ministers and permanent secretaries. At the Ministry of Education, his assistant ministers were Kilemi Mwiria, a career educationist and, like Saitoti, formerly a university lecturer. The other was Beth Mugo, a trained broadcaster who, while working at the State broadcasting station, the Voice of Kenya (VoK), headed the schools broadcasting section. Working with Saitoti as Permanent Secretary (PS) was another veteran in the education field, Karega Mutahi, a former primary school teacher who studied privately and became a university professor.

The team worked seamlessly and the members complemented each other. Those who worked closely with them indicate that it is the good chemistry between them that made it easier to implement the free primary education project.

At the Ministry of Internal Security, Saitoti’s Assistant Minister was Orwa Ojode, then Member of Parliament (MP) for Ndhiwa, who died in the same helicopter accident as the Minister. The PS was Francis Kimemia, a career administrator who had risen through the ranks from a district officer to PS. He was succeeded by Mutea Iringo, another veteran on security matters who had been transferred from the Defence Ministry.

Saitoti’s tragic death cut short an impressive career only a year before the next General Election.