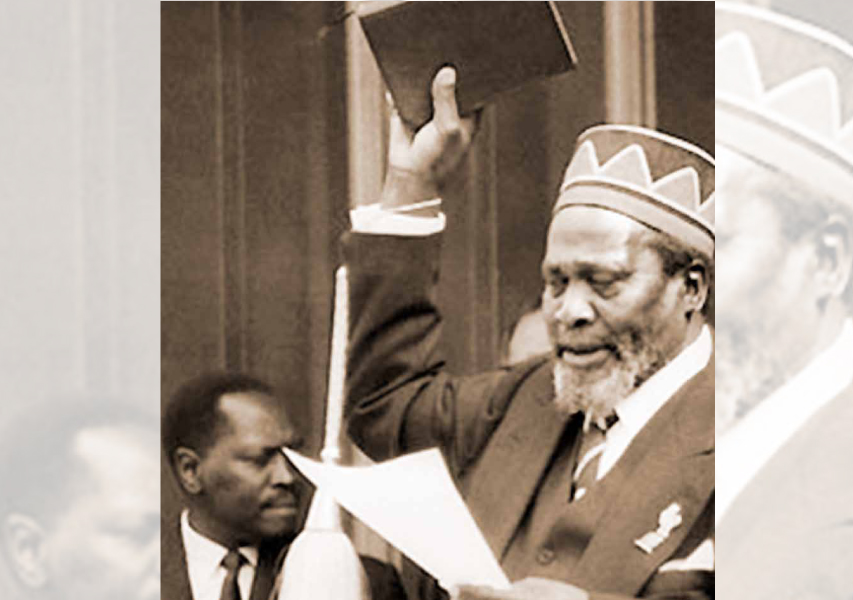

Kenya’s first President and Prime Minister, Mzee Jomo Kenyatta was an African statesman who rose from jail and house arrest to lead a new nation from 1963 to 1978.

Mzee Kenyatta was born Kamau wa Ngengi at Ng’enda in Gatundu, Kiambu, in the 1890s. His parents, Muigai and Wambui, died when he was young.

The orphaned Kenyatta received early cultural training from his grandfather, Kung’u wa Magana, a traditional healer, and later his paternal uncle, Ngengi.

From an early age, Kenyatta took interest in the Agikuyu culture and customs, learning the legends, kinship system and government. With little parental guidance, and aged slightly above 10, Kenyatta, who was then herding livestock, left his paternal uncle’s animals in the field and joined the Scottish Mission Centre at Thogoto, Kikuyu, where he worked as a cook.

It is at the Church of Scotland Mission at Kikuyu that he was baptised Johnstone by the Rev J. Soutter in August, 1914. Initially, he had gone for an operation on his leg. There are claims that he was suffering from a spinal illness and was operated on by Dr J.W. Arthur, “who probably saved his life”.

“After schooling, he brought me some money, a blanket and a piece of linen and we reconciled,” his uncle would later say.

Still in his early teens, Kenyatta underwent the Gikuyu rites of passage with the Kihiu Mwiri initiation group.

Kenyatta’s grasp of the English language, having lived with the missionaries at Thogoto from an early age, enabled him to rise from his underprivileged position. In his spare time, he helped in the first translation of the Bible into the Gikuyu language while still working as a cook at the mission.

He was later employed by J. Cooke to help in the kitchen. Cooke was nicknamed John Chinaman, for he could spin yarns like an old Chinaman. Besides working as a cook, Kenyatta received vocational training in carpentry and basic education in Bible study, English and arithmetic.

During the First World War, Kenyatta went to his relatives in Maasailand near Narok to possibly escape conscription into the colonial army. But he got a job as a clerk for an Asian trader in Narok. After the war, he became a storekeeper at a European company. At this time, he began wearing a beaded belt, kinyatta.

Shortly after the First World War, Kenyatta returned to Dagoretti to settle down.

In 1919, he married Grace Wahu, who bore him two children: Peter Muigai and Margaret Wambui. Muigai Kenyatta, MP for Juja and Assistant Minister for Foreign Affairs (1974-1979), was born in 1920 and died in 1979. Margaret Kenyatta, a former Mayor of Nairobi and a member of the defunct Electoral Commission of Kenya, was born in 1923.

Between 1921 and 1926, Kenyatta worked for the City Council of Nairobi’s Water Department as a meter reader for a monthly salary of Sh250, a lot of money at the time. He bought a bicycle and in one of his early pictures, he is captured with his son Muigai beside it, no doubt a sight to behold back then for an African.

Although he had a farm and a house in Dagoretti, he preferred to live closer to town, at Kilimani in a hut he had built. He cycled home on weekends. He was not yet openly engaged in politics since government employees were barred. But it is believed that Kenyatta had joined the Kikuyu Central Association (KCA) as early as 1922 and had registered as a member in 1924.

The force behind Kenyatta’s recruitment was the central Kenya politician James Beauttah, who carried on with the political work started by Harry Thuku, a pioneer trade unionist who had founded the East African Association before the colonial government banished him from Kiambu to Kismayu, Somalia.

Kenyatta’s supporters formed the KCA in 1924. In 1927, the association started a publication, Muiguithania (Reconciler), a title that reflected the fallout between local chiefs, religious leaders, traditionalists and activists within the KCA. It was also a forum to raise funds and recruit more people to fight the colonial inequalities and preserve the African cultural bond.

In 1927, Kenyatta joined the KCA leadership, which had problems with the translation of bulletins and memoranda into English. This was a turning point for the organisation. Because of his oratory skills, Kenyatta became the KCA secretary-general, with the duty of crafting and presenting KCA petitions to the colonial administration.

Muiguithania promoted the KCA manifesto with zeal and the European church missions were suspicious of its agitation for equality. But what was overplayed abroad was its attack on Christians over their stand on cultural values, especially female circumcision practised in Gikuyuland. It was in the KCA that Kenyatta was to hone his political skills. He was chosen to present the Gikuyu land problems before the Hilton Young Commission. In February, 1929, he left the country for England, much to the chagrin of the colonial government.

The Governor Edward Grigg asked the KCA if it was worthwhile wasting money on a mission the colonial government deemed impossible. But the KCA was determined to press on with the matter. Although in London he was not able to hand over his petition directly to the Colonial Secretary, the trip was an eye-opener for Kenyatta, who got useful contacts, among them William McGregor Ross, a former member of Kenya’s Legislative Council (Legco) and Director of Public Works. Ross had been forced to step down for dismissing settlers as corrupt and exploitative. Together, they discussed politics and struck good rapport. In the short period he was in Europe, Kenyatta visited Moscow and attended the International Negro Workers Conference in Hamburg, Germany, where he met a man who would be a lifetime friend, a West Indian trade unionist and writer, George Padmore, who would make a great impact on Kenyatta’s character transformation.

In September, 1930, Kenyatta returned home to a warm welcome and continued to challenge the Scottish Mission Church on female circumcision. He started working for the Kikuyu Independent Schools in Githunguri, Kiambu. But in November, 1931, he returned to England to present a written petition to parliament. So important was the event that he was escorted by a group of KCA members, including its president, Joseph Kang’ethe, to the Nairobi Railway Station to travel by rail to Mombasa and then by ship to London. Kenyatta was accompanied by a KCA official, Parmenas Githendu Mukiri, and by lsher Dass, who was to present a similar petition for the Indian community. The discrimination on the way to Europe via Mombasa appalled the two nationalists.

Kenyatta met Mahatma Gandhi of India, a man who eschewed violence as a means of winning political power. It is not clear whether this encounter influenced Kenyatta and was later the cause of his moderation in politics compared with the Mau Mau leaders. After giving evidence to the Morris Carter Commission, Kenyatta proceeded for Moscow to learn economics, but was forced to return to Britain in 1932. He enrolled for studies at Woodbrooke College, near Birmingham, and briefly stayed with anthropologist Norman Ley’s family, which had connections with Kenya.

It was from Woodbrooke that Kenyatta cut his teeth as an activist, writing articles, normally letters to the editor, for his favourite newspaper, the Manchester Guardian (now the Guardian newspaper), which had identified itself with the left wing liberals. How Woodbrooke changed Kenyatta is little known, but from then on he advocated equality of political rights as a KCA representative, a moderate association whose policies, according to Kenyatta, were chiefly “those of cooperation between the Agikuyu and the government on the one hand, and the Agikuyu and the white settlers on the other”.

At that time, the KCA was little understood. According to Kenyatta, the association stood for negotiation and he was quick to deny that it harboured any motive apart from what was expressed in its published literature.

Kenyatta cut short his studies at Woodbrooke to return to Moscow, stayed for a two-year stint and went back to Britain in 1934. In this period, the British intelligence started watching him with a keen interest, especially after his return from Moscow, partly because he shared a flat with South African writer Peter Abrahams and Paul Robeson, an African-American son of an escaped slave who was a popular civil rights activist, singer, athlete, actor, lawyer and film star. In 1933, Kenyatta had enrolled at the London University’s School of African and Oriental studies (SOAS) to study Kiswahili and other African languages. It was during this period that Robeson met Kenyatta and Kwame Nkrumah of the Gold Coast (now Ghana) and nudged them into embracing communism.

The British MI5 noted Kenyatta’s close relationship with the American shipping heiress, Nancy Cunard, who was a champion of black civil rights. One of the MI5 reports in December, 1933, says Cunard “has recently been associating — apparently with considerable satisfaction to herself — with Johnstone Kenyatta”. To the British Foreign Office, he seemed “a harmless individual if left alone, but apparently susceptible to outside influences”. Kenyatta was a well-known figure within his circle of friends, who viewed him simply as a dandy and had nicknamed him “Jumbo”.

In 1935, from his contacts in the film industry, Kenyatta and his friend Robeson played a brief part in an Alexander Korda film, Sanders of the River. But politics remained his main focus and when the Italians invaded Ethiopia, Kenyatta was so incensed that he broke through a police line in 1936 to embrace Haile Selassie when the exiled Emperor arrived at the Waterloo Station. Kenyatta had by then joined the University College London to work in the Department of African Phonetics and got to know leading journalists and commentators interested in African affairs. He developed an interest in writing about Gikuyu traditions and culture, supervised by the famous Polish anthropologist Prof Bronislaw Malinowski. Kenyatta not only enrolled in Malinowski’s anthropology class but also published, Facing Mount Kenya in 1938 under the name Jomo Kenyatta.

The book carried a photograph of a bearded Kenyatta with a spear and a blue monkey cloak slung over his shoulder, Malinowski’s idea being to make him look more like a tribal elder than a Western student. Kenyatta soon became an activist and would be seen around London’s Hyde Park or Trafalgar Square speaking to British crowds on African issues and denouncing colonial policies. In 1942, he published two more books — My People of Kikuyu and The Life of Chief Wang’ombe. In the same year, he married Englishwoman Edna Clarke, 32, and together they had a son, Peter Magana Kenyatta.

It was in 1945 that he helped to organise the Fifth Pan-African Congress in Manchester, which brought together important African leaders, among them Nkrumah. Shortly after Manchester, KAU sought Kenyatta’s return and in September, 1946, he came back to Kenya. Shortly after, he married Wanjiku, daughter of Kiambu Senior Chief Koinange, who died as she gave birth to Jane Wambui.

Wanjiku’s brother, Peter Mbiyu Koinange, would later become a very powerful figure in the Kenyatta government.

When Kenyatta returned, James Gichuru, a former teacher at the Alliance High School, was the KAU president. In June, 1947, he stepped down for Kenyatta, who started demanding the return of Kikuyu land that had been grabbed by white settlers.

The year 1951 was crucial for Kenyatta. In September, he married Ngina Muhoho, a daughter of Chief Muhoho.

In the same year, he started organising KAU meetings, met British Secretary of State for Colonies James Griffiths, and proposed a constitutional conference before May, 1953. KAU was torn between moderates and radicals and politics hit fever pitch with the emergence of the Mau Mau movement, which launched an armed struggle.

When the colonial administration could no longer stave off the wave of violence and discontent sweeping Kenya in 1952, the war council devised what it conceived as the final solution.

At an August 17, 1952, meeting to discuss emergency powers, the fate of prominent politicians deemed to be fuelling the “malevolent” wind of freedom over the past 18 months was sealed. The top security meeting was told a list had been prepared and that leaders such as Jomo Kenyatta were to be arrested, even though the officials knew they could not sustain any charges against them.

Top secret papers the British government was recently forced to release in London indicate the colonial administration knew all the evidence it had against the politicians was wishy-washy and could not support charges even in a “quasi-judicial proceeding”.

This notwithstanding, E.R. Davies of the Native Council, told the 1952 meeting that he was determined to “put Kenyatta away by some means or other under the present law”.

Frustrations by the administration’s inability to dispense justice as fast as they wanted is summed up by one Nairobi magistrate, quoted in a circular dated September 12, 1952, complaining that some witnesses were even dispatched for holidays in undisclosed destinations when they were expected in court, making them unavailable to testify.

Before this, a plot had been hatched to hold a big anti-Mau Mau meeting in Kiambu by the local District Commissioner, N.F. Kennaway, on August 24, 1952, which elders and church leaders would attend.

Kenyatta, the senior government officers were told, had already been roped in by David Waruhiu and Eliud Mathu and had promised to disown Mau Mau in the meeting.

The Government was growing impatient about its inability to convict suspected Mau Mau adherents and sympathisers because witnesses had the habit of refusing to testify even after recording statements with the police.

The Criminal Investigations Department too was frustrated by the lack of cooperation. It cites the case of Moris Mwai Koigi who publicly bragged to 300 listeners how he had administered Mau Mau oath but none could be persuaded to testify against him.

Chief Nderi Wang’ombe of Nyeri who wanted to testify received a letter on the day of the hearing, warning him of dire consequences should he betray his people and country. The chief was later killed.

The judiciary also altered the rules to allow changes on charge sheets during any stage in trial, to save the Government the embarrassment of losing a case as a result of defective charges.

In the meantime, the tension which had been building up in the country reached a boiling point on October 9, 1952, when Kiambu Senior Chief Kung’u Waruhiu was gunned down in broad daylight just as the recently posted governor, Evelyn Baring, was on a tour of Central Province.

Kenyatta attended the funeral together with Governor Baring, amid threats to his life by White settlers.

Chief Waruhiu’s killing changed the political landscape and gave the Government the perfect excuse it had been seeking to round up all the political undesirables. On the night of October 20, 1952, the operation dubbed “Jock Stock” struck.

Kenyatta and five other politicians, Kung’u Karumba, Achieng Oneko, Fred Kubai, Paul Ngei, and Bildad Kaggia (famously known as the Kapenguria six) were seized in the crackdown, which marked the start of a state of terror in Kenya, as thousands were arrested and detained after a state of emergency had been declared. Erstwhile government allies were not spared either. Government security forces arrested ex-Senior Chief Koinange wa Mbiyu and his son John Mbiyu in connection with Waruhiu’s murder. The government also started executing a system of disinheriting the seized leaders of their land.

When the issue of political repression arose in Britain days before the declaration of the State of Emergency in Kenya, the Secretary of State for Colonies, Oliver Lyttelton, told Parliament on October 16,1952, that some laws were needed to intimidate the Mau Mau.

According to Lyttelton, as quoted in the Hansard, Mau Mau was a secret society confined to the Kikuyu, an offshoot of the KCA, which had been proscribed in the 1940s.

The Kapenguria Six were charged with managing Mau Mau. Despite the legal defence by Denis N. Pritt, Diwan Chaman Lall — an Indian MP sent by Prime Minister Nehru — Kenyan-Indian lawyers F. R. S. De Souza and A. R. Kapila and Nigerian advocate H.O. Davies, the six were in April, 1953, each sentenced to seven years hard labour and indefinite restriction thereafter. Their appeal to the Privy Council was also turned down in 1954. Kenyatta completed his sentence at Lokitaung, nearly 800km from Nairobi to the north, in 1959 and was restricted at Lodwar, 430km from Nairobi, where his wife, Ngina, joined him.

The release from jail of Dr Hastings Kamuzu Banda in Malawi in April, 1960, set off a new demand for Kenyatta’s release from restriction, though Oginga Odinga had started the campaign on the floor of the Legislative Council (Legco) in 1958. Back in London, Colonial Secretary Ian Macleod was weighing all the options, although the Governor in Nairobi, Patrick Renison, was hesitant to release Kenyatta, a man he would later describe as a “leader unto darkness and death”.

While the colonial government wanted to accelerate changes without Kenyatta, the African leadership, led by Odinga and Tom Mboya, wanted Kenyatta back to lead the independence phase. In 1960, Ambu Patel, a follower of Mahatma Gandhi, formed the Release Jomo Committee to whip up public support. By April, he had collected numerous signatures in a plea for Kenyatta’s release, which the Nairobi People’s Convention Party presented to the Governor. The election of Kenyatta as Kanu president in absentia and the birth of Kadu, bringing together the so-called small tribal parties, transformed the political landscape. The “No Kenyatta, No Legco” campaign continued and Kenyatta was moved from Lodwar in northern Kenya to Maralal, about 90km apart, in April, 1961, where he addressed a press conference, his first in eight years. Four months later — on August 14, 1961 — he returned to Gatundu and in October was installed as the president of Kanu. For Kenyatta to be a member of Legco, Kigumo MP Kariuki Njiiri stepped down and Kenyatta was elected to the Legco. Kenyatta then led the 1961 and 1962 Kanu delegations to the Lancaster Constitutional Conference in London.

With Kenyatta’s leadership, Kanu grew into a mass party, transcending all expectations. In May, 1963, Kenyatta led the party to an electoral victory and subsequently formed the Government as Prime Minister on June 1. This is celebrated as Madaraka Day. Madaraka is a Kiswahili word, which means self-management. With Kenya’s economy depending on colonial farming, Kenyatta was caught between sustaining growth and appeasing his supporters. The question of land was to be a tinderbox in his regime. A clear policy on the landless was one of the early tests that Kenyatta faced as Prime Minister. It was felt that land transfers should be orderly lest it caused panic and destroyed the economy.

Kenyatta managed to balance between the different interests and when Kenya got independence in December, 1963, and became a Republic in 1964, he became the first President, bringing the mandate of the Governor-General, Malcolm McDonald, to an end.

Kenyatta used his political acumen to convince leaders of the opposition party Kadu to cross the floor to the Government side without having to go for by-elections.

The merger of Kanu and Kadu had the effect of consolidating Kenyatta’s power and gave him all the powers to run the State and control its organs. He became the ruling party Kanu’s chief, was the head of the only political party, the head of State and the Government and Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces.

A policy document — Kenya African Socialism: Its Application to Planning in Kenya (better known as Sessional Paper No. 10 of 1965) was also passed to balance between the different thinking within Government.

Revered as Baba wa Taifa (Father of the Nation) and fondly referred to as Mzee (old man), Kenyatta held the country together despite the numerous internal and external challenges he faced. The economy grew at an average rate of five per cent annually between 1963 and 1970, and eight per cent every year from 1970 to 1978.

The growth followed measures taken to distribute productive land to small-scale farmers and promotion of the cultivation of cash crops such as tea, coffee, and hybrid maize, as well as the development of dairy farming. As a result, rural incomes rose by five per cent annually from 1974 to 1982, and the smallholders’ share of coffee and tea production rose to 40 and 70 per cent respectively by 1978.

Under Kenyatta, State parastatals and institutions were alternative wheels of development. He died on August 22, 1978, at the State House Mombasa.