William Cheruiyot Morogo’s Cabinet colleagues talk about a gentleman who got along with colleagues as well as backbenchers in the House. “He respected all and never promised what he couldn’t do,” recalled Stephen ole Ntutu, a former Minister for Tourism, while Philip Chebogel, a friend and former classmate, said, “He was a humble man who was easily accessible to all. He didn’t segregate. He worked for those who voted for him as well as those who didn’t.”

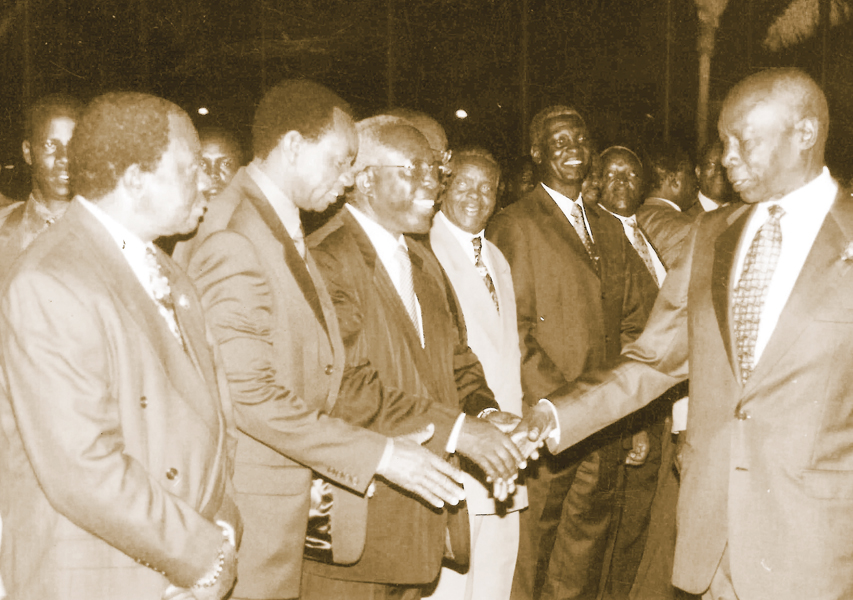

Morogo was the Minister for Roads and Public Works from 2000 to 2002 and was elected to Parliament for 10 years – from 1992 to 2002. In 1992, President Daniel arap Moi backed Morogo’s bid for the Baringo South parliamentary seat. The President and Morogo’s father, Chebet arap Lagat, who had worked as a colonial chief, met in the 1950s. At the time, Moi was in the Legislative Council representing Rift Valley. The two remained friends even after Moi became President. When, in 1992, arap Lagat (as Morogo’s father was popularly known) requested him to support his son’s bid to enter Parliament, Moi agreed.

Morogo, who is now 73 years old, attended Kisanana Primary School up to Standard Four, when he sat for the Intermediate Examination. He then joined Tenges Secondary School where he studied accounts. After Tenges, he helped his father to manage the family farms and businesses in various parts of Baringo and Nakuru districts (both are now counties).

When the Rift Valley Institute of Science and Technology was established in Nakuru in 1979, Morogo was employed as an accountant until his entry into politics in 1992, when he successfully vied for the Baringo South seat. When Mogotio and Eldama Ravine constituencies – both of which were hived out of Baringo South – were established in 1997, Morogo moved to the former, contested and won despite stiff competition.

“His loyalty to Moi and the long friendship his father had with the former President were instrumental in his decade-long stay in parliamentary,” said Chebogel.

Ntutu recalled that as Minister for Roads, Morogo spent much of his time on the ground inspecting roads that were under construction to ensure that they were built according to specifications. Most of these roads are still in good condition 17 years after the minister left office.

“He ensured that all roads that were earmarked for upgrading or improvement were completed on schedule,” said Ntutu.

William Lotodo, a former Baringo East MP, confirmed that Morogo left an indelible mark on the development of road infrastructure in the country and added that even though his actions did not attract much media attention, he achieved a lot in repairing roads that had been in a sorry state for many years. “What he achieved was never highlighted. He was controversy-shy but a hard-working person. He upgraded roads even in the remotest parts of Kenya, such as my former constituency,” Lotodo said.

Today, those roads are being used even by security personnel to fight banditry. “Banditry thrived in the absence of roads. It is now much easier to tackle because the areas are accessible.” Chebogel said the former minister took advantage of his relationship with Moi to ensure that electricity reached rural areas such as Kisanana, and to sink several boreholes in the arid Mogotio Constituency. Yet despite Morogo’s cool and easygoing demeanour, he kept a close eye on his political opponents.

“He had his finger on the pulse of his constituency. He kept tabs on everything that was happening. Although he wasn’t outspoken or violent, he closely monitored his opponents.” As MP, Morogo tried to sort out land ownership wrangles in the constituency. A case in point is the Banita Sisal Estate, an expansive farm whose lease expired more than three decades ago. The farmland was being claimed by two ethnic communities in the area, each claiming it had been ancestral property before an Asian investor acquired it for sisal production.

Morogo also faced a challenge in ensuring that hundreds of acres in Alfega and Majani Mingi sisal estates, which had been in the hands of foreign investors, reverted to locals when the investors started to leave with the collapse of the sisal sector in the country. In the 2002 General Election, Morogo failed to clinch the KANU party nomination, which went to Joseph Korir, a former Nairobi Province Deputy Provincial Commissioner.

John Changwony, a businessman from Mogotio township, recalled how difficult it was for the former minister to accept his loss. “He believed he had done a lot for his people and couldn’t believe it when they showed him their backs.”

After quitting active politics, Morogo now leads a quiet life in Kisanana.