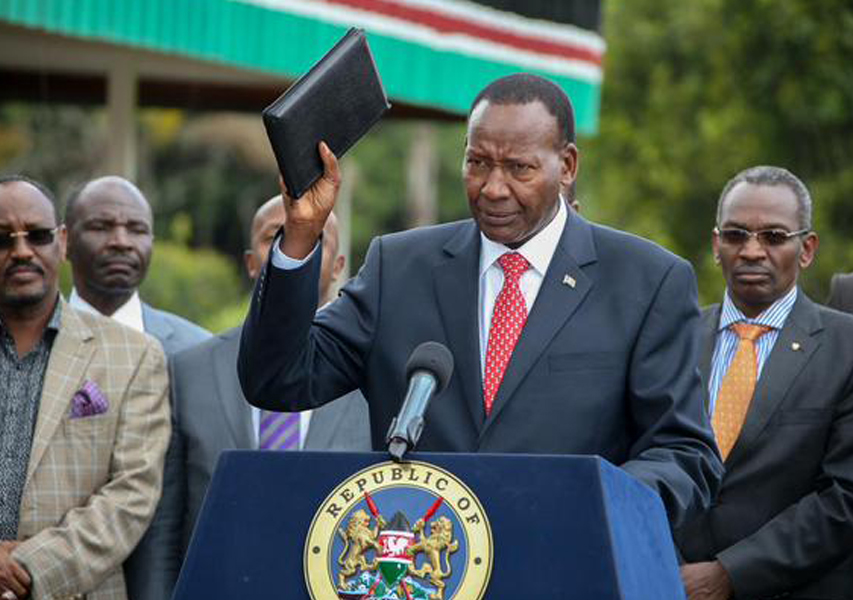

Tall, fierce and regal. That was Major General (Rtd) Joseph Kasaine ole Nkaissery, just the man President Uhuru Kenyatta needed to rein in runaway insecurity that threatened to mar the running of the government he had just inherited from Mwai Kibaki.

As a retired soldier Nkaissery came highly recommended. The no-nonsense disciplinarian who had served in the Kenya Defence Forces for 30 years in various ranks had also been an Assistant Minister for Defence in the Grand Coalition Government of President Kibaki and former Prime Minister Raila Odinga.

Killings in Mandera, Mombasa and Nairobi by the Somalia-based militia, Al Shabaab, as well as bandit attacks in places such as Kapedo on the border of Turkana and Baringo counties, had given Uhuru a constant headache. He needed a firm hand in the Security docket and was willing to look across the political divide for a solution. He found in Nkaissery a person who fit the bill. In December 2014, Nkaissery, an Opposition MP in his third term, was appointed Cabinet Secretary for Interior and Coordination of National Government.

He was coming into a sector that was scarred by lethargy, decrepit coordination and flagrant corruption. The Kajiado Central MP, who had been elected on an Orange Democratic Movement ticket, was the first Opposition MP to be handed such a key position since Kenya adopted a new Constitution in 2010.

Uhuru and Nkaissery actually went way back — to their days in the Kenya African National Union (KANU) party through which the MP was first elected in 2002 and which the President served as chairman before becoming the KANU presidential candidate when he made his first unsuccessful stab at the presidency.

In appointing Nkaissery, a man with a deep knowledge of security issues and considerable political anchorage, the President was shifting gears from the largely technocratic Cabinet he had appointed in 2013 — in line with the 2010 Constitution — to leaders more in tune with State affairs. Nkaissery was replacing Joseph ole Lenku, a languid hotelier from the General’s Kajiado County backyard, who had been relieved of his duties after a series of terrorist and bandit attacks that had rocked the country.

At the very onset of his tenure, Uhuru had inherited an enemy in the name of Al Shabaab – a ragtag army operating out of Somalia that had kidnapped a number of tourists on Kenyan beaches. The tourism industry, especially on the Kenyan coast, took a hit as foreign governments advised their citizens against visiting Kenya because of the rising state of insecurity and the government’s seeming helplessness in combating it.

In September 2013, barely five months after Uhuru took over from Kibaki, terrorists staged a daring attack at Westgate Mall in upmarket Westlands, Nairobi. Close to 70 people were killed in the attack and more than 175 were injured. Then in early December 2014, 36 quarry workers were killed by Al Shabaab militants in Koromei, Mandera County. The attackers targeted non-Muslims. A week earlier, on November 27, militants had commandeered a bus in Mandera County and killed 28 passengers, most of them teachers.

As the attacks endured, the Opposition and a sprinkling of ruling party MPs called for an overhaul of the security agencies and the dismissal of Interior CS Lenku and Inspector General of Police David Kimaiyo. Lenku was sacked and Kimaiyo resigned on the same day, to be replaced by spy chief Joseph Boinett.

Nkaissery assumed the role with zeal, promising to serve diligently and to rally security officers behind him.

“If you know you are a security officer earning a salary from taxpayers, then you must be ready to work and offer services for which you have been trained. Those who feel they cannot do that are free to walk,” he said after his appointment.

Despite the tough talk, it was not an easy ride for the soldier. He soon found himself in the eye of a storm as the Opposition and civil society organisations expressed outraged against the Security Laws (Amendment) Bill 2014, which were fast tracked in response to the terrorist attacks on civilian targets and mounting public pressure to curb crime.

The Opposition, human rights organisations, including the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights, and the Independent Policing Oversight Authority objected to the far-reaching amendments, which they said would add new criminal offences with harsh penalties, limit the rights of arrested and accused persons, and restrict freedoms of expression and assembly. Nkaissery defended the enactment of the new laws, saying they would offer a framework to secure basic rights guaranteed in the Constitution.

“I want to assure Kenyans that we will not infringe their human rights and fundamental freedoms. We will ensure that Kenyans gain confidence in security operations,” he maintained.

The Security Laws (Amendment) Act No. 19 of 2014 (SLAA) was passed by the National Assembly on 18 December 2014 and got presidential assent on 19 December 2014.

Nkaissery promised to initiate reforms and restore Kenyans’ confidence in the government’s ability to surmount the insecurity that had ravaged the country. But waiting around the corner for him was an incident of grim proportions. On 2 April 2015, an attack on Garissa University left 148 people, mostly students, dead. Nkaissery promised to get to the bottom of the matter and warned Al Shabaab, the suspected masterminds, thus: “You can run but you cannot hide, and we will get you.”

Security expert George Musamali noted that during Nkaissery’s tenure, the Al Shabaab were driven to the Somalia border where their strength was compromised. He said Nkaissery was able to coordinate the various security agencies to achieve this. But Musamali faulted the CS for not focusing on the welfare of the police.

“He also picked weapons that were not suitable for the terrain and did not address the issue of extra-judicial killings,” said the former Recce Squad commando.

Nkaissery was born on 28 November 1949 and attended Ilbisil Primary School between 1960 and 1966 before joining Olkejuado High School from 1967 to 1970 for his O’ levels. In 1971 he was part of the pioneer class in the Department of Education at Kenyatta College. After only one year, he opted to join the Kenya Army and attended the Kenya Armed Forces Training College in Lanet. In 1996, he was chosen for a leadership and development course at Harvard University’s Kennedy School in the US. The United States Army College later accepted him for a postgraduate diploma in strategic leadership and management.

Back in Kenya, the man in uniform rose through the ranks from Battalion Commandant in 1982 to Battalion Second in Command in 1986, Military Assistant to the Chief of General Staff from 1987 to 1991, Chief of Personnel from 1992 to 1993, Brigade Commander from 1994 to 1996, Deputy Commandant/Chief Instructor-Brigade from 1997 to 1998, and General Officer in Command-Westcom from 1999 to 2002.

It was soon after his retirement that members of Nkaissery’s Maasai community prodded him to venture into politics. That was how he ended up being MP for Kajiado Central from 2002 to 2013. As Assistant Minister for Defence in the Kibaki-Raila coalition government, he was particularly outspoken on issues pertaining to the Maasai community, especially after the death of William ole Ntimama, a former Cabinet minister and the undisputed spokesman for the community until his death.

In December 2016, Nkaissery outlawed 90 groups that had been categorised as organised criminal gangs operating in various parts of the country. The groups included 42 Brothers, Magufuli Gogo Team, American Marines, China Squad, Baragoi Boys, Chapa Ilale, Rambo Kanambo, Gaza, Wakali Wao and Taliban Boys. Others were Kawangware Boys, Islamic State, Vietnam, Ngundu River Boys, Tek Mateko, Nzoia Railway Gang, Eminants of Mungiki and Temeke.

As the 2017 General Election approached, Nkaissery appeared to be a man at peace with himself. The country was no longer a playground for Al Shabaab and the avowed football fan, who supported Premier League team Manchester United, could afford to crack jokes.

Then on 8 July 2017, with a month to go before the elections, Nkaissery suddenly fell ill and died a few hours later. He was 68.

His death shocked the nation, with the President revealing that he had spoken to the CS the previous evening. Earlier, Nkaissery had attended the National Prayer Rally at Uhuru Park, Nairobi, with the President, Third Way Alliance presidential candidate Ekuru Aukot, and Michael Wainaina, an independent candidate. At 10pm, Nkaissery arrived at his Hardy Estate home in Karen, Nairobi, and headed to his private gym before retiring to bed. At 1am he was reported to have woken up complaining of a sharp pain in his chest before collapsing in his house. He was pronounced dead on arrival at Karen Hospital in Nairobi on the morning of 8 July. Post-mortem results showed he had suffered from a heart attack.

“I personally have lost a friend, a colleague, with whom as late as yesterday I spent part of the day praying for peace for this country; with whom as late as 9:30 last night I was discussing issues pertaining and relating to peace, to unity in this country,” said Uhuru while officially announcing the CS’s death.

It was not only the government that felt the loss. For the Maasai community, a huge gap had been left.

“Nkaissery’s death leaves a huge leadership crater,” said Maasai historian Sironka ole Masharen. “By design he was the most powerful Maasai. Just as Collin Powel was the most powerful Black man on earth at a time when Mandela was the most popular,” Masharen told the Daily Nation.

Masharen’s dialectics of the popular versus the powerful revealed another side of the CS — resolute and ruthless. Nkaissery was a major in the army in 1984 when he was deployed to disarm locals under a programme named ‘Operation Nyundo’. According to a Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission (TJRC) report, gross violations of human rights were perpetrated by soldiers in what came to be known as the Lotirir Massacre.

The matter emerged during Nkaissery’s vetting in the National Assembly following his nomination as CS. The TJRC report alleged that the security agents used heavy artillery and bombed villages, and that the operation resulted in torture, sexual violence and killings. It also alleged that the operation led to the killing or confiscation of up to 20,000 head of cattle.

The CS disputed this version of events, arguing that it would have required 500 lorries to transport 10,000 head of cattle, not to mention the unforgiving terrain that would have made such an endeavour impossible.

Masharen also described Nkaissery as principled and incorruptible. “He was a quintessential Maasai archetype, exactly what early white anthropologists described as tall, elegant, handsome, honest, resolute and militant.”

Unfortunately, his death denied Kenyans a fuller picture of what he would have done for President Uhuru Kenyatta’s legacy and the country at large.