Before coming to the national limelight, Hassan Gurach Wario Arero cut his teeth in academic research, accumulating experience from Kenya and England, where he had also earned one of his academic accomplishments as a Chevening Scholar at the University of East Anglia.

A social anthropologist by training, Wario’s place in the public sphere represented many groups — the youth who traditionally had been pushed to the fringes of national government, people from the wider north-eastern communities that similarly lived on the peripheries of the political limelight, and the academics plying their trade outside the university system.

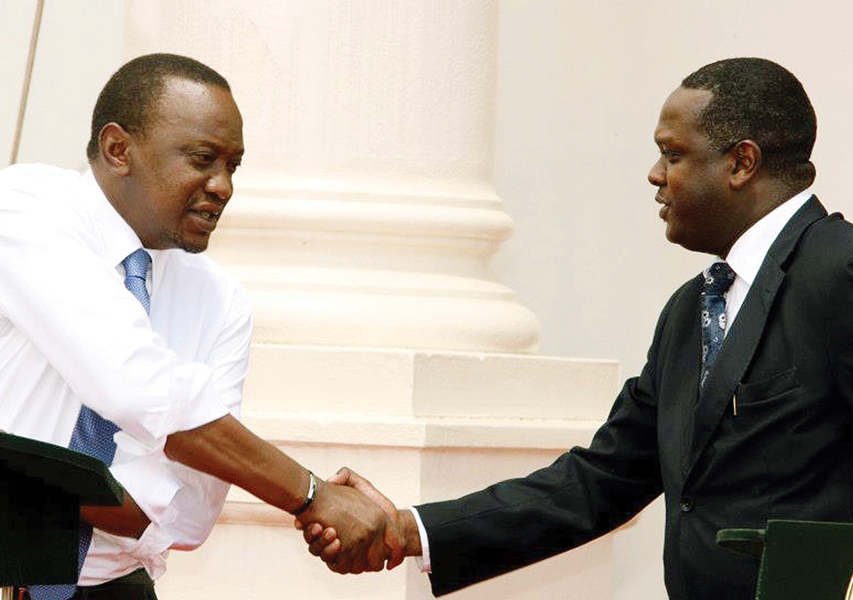

Such was the anticipation among many that Wario’s youthful outlook, charming demeanour and razor-edge intellect would inject something new into the Ministry of Sports, Culture and the Arts, which he was appointed to head soon after President Uhuru Kenyatta’s hard-fought victory in the presidential race.

It was a new era into which Wario walked as he learnt the ropes of senior government administration, overseeing an amalgamated and omnibus ministry that was simultaneously associated with the youthful athleticism of sports, and the reactionary conservatism of patriarchal traditions of yore, enveloped in the ambivalent term of culture, both intersecting at the complicated terrain called the arts.

Born in 1970 during the last decade of Jomo Kenyatta’s presidency, Wario came of age, coincidentally, in the last decade of President Daniel Moi’s regime when he, Wario, graduated in 1995 from the University of Nairobi with a Bachelor of Arts Degree in Anthropology.

It is conceivable that, being a university student during the tumultuous days of the multiparty struggle had exposed him to a pro-change and pro-youth perception — a different perspective of the same point, really — with which he went on to chart his career path.

At the time Wario graduated from the University of Nairobi, academia had witnessed and survived shifts in trade unionism among the intellectuals, whose luminaries such as Korwa Adar, Walter Oyugi and Kilemi Mwiria — who later joined elective politics and served in President Mwai Kibaki’s Cabinet — among others, had been fire-breathing advocates of a human rights approach to national discourses.

From the early 1990s onwards, the winds of change that blew across the whole spectrum of public life in Kenya could well have been a key factor that persuaded Wario and many of his generation to consider further studies as a pathway to a career in academia.

It is also plausible that the global media attention to the persecution of the academics such as Adar and Mwiria, who sought to mobilise university lecturers under a recognised trade union, also sparked the generosity of spirit among many institutions of higher learning in Europe, America, South Africa and the rest of the world.

Indeed, and not to take away from Wario’s intellect, he benefited from a scholarship and proceeded to the University of East Anglia for a master’s degree that he earned in 1998 and, in 2002, a doctorate in Social Anthropology.

Between 1995 and 2002, Wario worked at the National Museums of Kenya as the Head of Ethnography, tasked with the duty to identify, document and preserve aspects of material culture from different communities in Kenya. Not only did he initiate a policy on curating material cultures from across the country but he also imbued a sense of contemporaneity to a profession that had been associated with archaism.

Armed with such skills and propelled by this presencing of the past, Wario proceeded to serve as the Keeper of Anthropology at the Horniman Museum in London between 2002 and 2007, and then as the Curator of African collections at the venerated British Museum in London between 2007 and 2010. Only then did he return to Kenya to his previous employer where he now served as the Director of Museums.

It was from this position that Wario was deployed as Cabinet Secretary (CS) to the Ministry of Sports, Culture and the Arts.

As it was conceptualised, the ministry had a wide scope that touched on diverse interests. It was meant to develop and coordinate sports, promote and develop sports facilities, develop sports industry policy, and see to the development of a sports academy in Kenya with a view to expanding the sports industry in general. The ministry was also tasked to promote and diversify sports in Kenya beyond the most popular ones and formulate a policy on sports management.

In the realm of material culture, the ministry’s mandate included: to formulate a policy on national culture and promotion; design and develop a national heritage policy, and another policy on effective running of the Kenya National Archives and the management of public records in general. On heritage, the ministry was charged with managing the national museums and monuments, and historical sites.

Similarly, in terms of intangible and creative cultures, the ministry had the mandate to develop fine, creative and performing arts; the film industry; and lead in the formulation and implementation of the film development policy geared at promotion of local content. All these would then intersect at the points of promoting library services and research and conservation of music.

Viewed broadly from this standpoint, the appointment of Wario to this ministry was an extension of the same domain of knowledge industry in which he had worked all his life. The only difference was that, while at the ministry, he had the benefit of drawing on the experience of veteran administrators in the persons of Joe Okudo, who served as the Permanent Secretary for Sports, and Josephta Mukobe, the then Permanent Secretary in charge of Culture and the Arts.

Wario’s work was, in this manner, well cut out. He was entrusted with a ministry that had a way broader mandate than the ‘traditional’ sports portfolios, perhaps partly due to the strictures of the 2010 Constitution that prescribed the maximum number of ministries that a government could have.

That is how the Ministry of Sports, Culture and the Arts was structured around several departments, while ceding remarkable ground — which it oversaw nonetheless — to some semi-autonomous agencies, notably Sports Kenya, Kenya Academy of Sports, National Sports Fund, National Museums of Kenya, Kenya Cultural Centre and the Kenya National Library Service. Others were the National Heroes Council and the Anti-Doping Agency Kenya.

Not only was Wario expected to navigate the rather messy trenches of sports politics in their local and international contours, but he was also expected to breathe life into new departments within his ministry that had been somewhat dormant. A particular challenge was in harmonising the rather diverse interests and traditions that the diverse departments were traditionally associated with, while ensuring that the general public’s interests in these departments were met.

A particular challenge related to dwindling fortunes of national teams in some the most popular sports, including athletics, football, rugby and swimming. While the dipping performance of national teams in these sports could be explained by the rising influences of other variables, stock accusations of lacklustre government support highlighted what Wario and his team were doing to ensure that Kenya regained its pride of place as a sports powerhouse in the region.

At the time, self-help remedies in sporting activities had become so rampant that they entrenched the narrative of government abdication in supporting sporting activities, and fanned the flames of nostalgia among those who were old enough to recall bygone days when government support for sports was, in their view, without doubt.

This outlook had seen certain sports, mainly football and athletics, transform to theatres of big boy egos, cartels and varying forms of racketeering that had stained the image of these sports as social events, healthy spaces of socialisation, and potential career pathways for Kenya’s youth.

It was also the time when European football, complete with its complementary cultures, had superimposed itself on the national psyche of youthful and not-so-youthful Kenyans, perhaps to fill the gap that had been left by slackening standards in sports generally, but in football and athletics especially.

At the same time, there were lingering questions in the hearts and minds of another demographic of Kenyans, those who plied their trades in the humanistic scholarship — practitioners and teachers of music, film, theatre and performance, among others — who lamented the continued marginalisation of their areas of expertise from national debates on development and nation formation.

As part of the debates on where Kenya lost its soul in the aftermath of the 2007 elections, it became apparent that the arts, whether in film or music, play a critical role in imbuing among us a sense of togetherness, of a shared belonging, and of collective mutual implication in the plight of Kenya should anything happen to the country. All such practitioners and academics in the creative arts and keepers of national memory — as well as the consumers of their products — wanted was a chance to mainstream their thoughts and deeds in everyday national debates and business of government. For all these people, the mere act of having a ministry with the words ‘culture’ and ‘arts’ was a turning point in redefining the roles of these critical aspects of our being in the context of nation building. It was a moment of abundant hope for all these players.

All these dynamics comprised the stark reality that confronted Wario when he was appointed as CS of Sports, Culture and the Arts. He was well aware of the urgent need to align his pedigree as an academic-turned-administrator of a government department with the new government’s determination to put sports, culture and the arts at the centre of government — including turning the tide of perception of these sectors as tangential to national economic development — and of national discourses.

In practical terms, Wario’s task boiled down to heading a ministry that would help Kenya reclaim her slot in the international community as a sporting country of no mean pedigree, by restructuring the way sports was conceptualised and operated. He was also tasked to boost the place of culture and the arts in upholding Kenyans’ view of themselves, and generally nurture creativity and innovation across sports and cultural engagements by formulating and implementing progressive policies.

Apart from addressing the routine challenges of sports infrastructure, Wario was also expected to confront the software issues afflicting sports in general. Not least among these were the issues that characterised every sport by way of all kinds of corruption, accusations of favouritism, cartels, sabotage from within, and increasing bad press regarding the seemingly routine accusations levelled against Kenyan athletes of involvement in dubious schemes of steroid-assisted victories.

Also expected was the delivery on the ambitious commitment by the Uhuru government to deliver stadiums across all the counties in Kenya, building some from scratch, while refurbishing others to modern standards. Some of these were done, notably the Nyayo National Stadium and the Kasarani International Sports Centre, both in Nairobi. Others were the Bukhungu Stadium in Kakamega.

These facilities spoke favourably of a regime that took sports seriously, a statement also made by the fact of Kenya’s presence on the international arena where, despite several hiccups, the country continued to assert its presence.

Wario also leveraged on the Uhuru government policy pronouncements to deliver on his mandate. For example, to address the perennial problem of underfunding for national teams in sports, the government established the National Sports Fund through the Sports Act 2013 (Section 12 of Part III), which played a critical role in fundraising to support sporting activities through underwriting a cash-award scheme for exemplary performance, training sports personnel, and the general growth and development of sports. At the same time, the fund was deliberately linked to Vision 2030 and mainstreamed in the first and second Medium Term Plans, an indication of the Uhuru government’s commitment to boost the sports industry in the context of wider economic development policies and programmes.

With the help of the National Sports Fund, Kenya continued to participate in larger numbers in major international championships including regional (CECAFA, for example), continental and world championships, such as the Commonwealth and Olympic games, and paralympics and deaflympics.

Also noteworthy is that the fund, under the leadership of Wario, contributed to the diversification into sporting disciplines, including ‘the Yego phenomenon’ in javelin.

Backed up by the expertise of then Okudo, the CS oversaw these developments that, sadly, would later be overshadowed by unbecoming conduct by some senior officials during the 2016 Summer Olympics in Rio di Janeiro. Not only did the misconduct highlight the challenges of organising national participation at that level of a sporting extravaganza but it was also a chance for government agency’s to demonstrate the President’s determination to strike the hydra-headed menace of corruption and its attendant downsides, mediocrity and all.

Obviously, some of the challenges that Wario encountered at the ministry outlived him there, and comprise the bulk of criticism regarding the seemingly endless moral decadence that is associated with sports management in Kenya. However, the Uhuru government purposefully adopted a zero-tolerance stance towards such malfeasance, and now individuals are being held accountable for their preconceived or inadvertent errors in character.

In the culture department, Wario’s tenure was equally busy in recognising and enabling the traditional institutions of cultural affirmation for the country in general. As was the case during his tenure at the National Museums of Kenya, the CS recognised immediately the value of people’s involvement in collective expression through their material, social and creative cultures.

In this regard, Wario’s tenure at the ministry saw a strategic revamping of institutions of culture and memory, including the whole Department of Culture, the Kenya Cultural Centre, and the National Archives and Documentation Services that, among other things, is the custodian of cultural and artistic artefacts of great historical and heritage value to the country. For example, the art collections associated with former Vice President Joseph Murumbi were curated and placed at an exhibition during Wario’s tenure; the Kenya National Library Services broadened its network and spruced up the facilities available, and the Kenya Film Commission partnered with players in other line ministries and academia to launch the annual schools, colleges and universities film festival as a filmic variant of the more established Kenya Schools and Colleges Drama Festival.

Other initiatives stood out, including the refurbishment of the Kenya National Theatre and its reintroduction to the national imaginary as the central space for cultural thought leadership and repository of creative memory; the broadening of collaborative networks to entrench film as part of Kenya’s creative cultures; and the involvement of the Kenya Film Committee in amplifying the opportunities within film for the youth and other Kenyans.

In all these, the traditional associations of this ministry with dreary activities of the everyday life gave way to more contemporaneous reckoning with topical issues of the day. This is how, as part of national debates on the question of our national values, some criticism arose targeting some of the regulatory interventions overseen by departments of government that are domiciled in the ministry.

For illustration, some people argued that the Kenya Film Classification Board and the National Cohesion and Integration Commission, which called out some artists for either indulging in hate speech or obscenities, were merely a decoy for the reintroduction of censorship, encroachment on the freedoms of expression, and an imposition on everyone an outdated form of morality upon a people more connected with the rest of the free world.

Other critics lamented that such agencies were merely playing to the political gallery of correctness while completely ignoring the creativity that went into these works, or being ignorant of how art works.

Whatever position one takes, it is clear that the mere merging of the ministry with aspects of arts and culture was a critical move in creating visibility for areas that had for long been subsumed in more established portfolios, such as education. Perhaps, it was the reification of these departments within the ministry that explains the phenomenal growth in the arts and how they dovetail into memory making, nation formation and the like.

The developments in the three priority areas of sports, culture and heritage, and of library and records, have been tremendous since Wario was appointed as CS in charge, and even after his departure to join the diplomatic service.