On 26 April 2013, President Uhuru Kenyatta and Deputy President William Ruto addressed an anxious nation at State House Nairobi. Two days before, they had named only 4 out of an expected 18 nominees for the position of Cabinet Secretary. This had created a sense of suspense as the new administration was the first tunder the 2010 Constitution, which demanded a raft of changes in the formation of the Cabinet, including names, numbers and selection procedures.

Under the Constitution, Cabinet secretaries (formerly referred to as ministers) were required to be apolitical professionals. They would no longer be Members of Parliament (MPs) but technocrats, whose primary brief was to effectively deliver on their mandates, using their expertise and aptitudes in their respective dockets. As such, it was obvious that the task of scouting for the right people to fit the bill was no small one.

As the two leaders named the four nominees on 24 April 2013, the President said they were still meeting with many brilliant Kenyans as they sought to fill the positions with the requisite capacity to implement the Jubilee Party manifesto. The first four to be named were Dr. Fred Okengo Matiang’i (for the Ministry of Information, Communication and Technology), Henry K. Rotich (Finance and Planning), James Macharia (Health) and Ambassador Amina Mohammed (Foreign Affairs).

In corporate-esque style, the President described the rich curricula vitae of his nominees as the basis for their qualifications, sharing details that Kenyans had not really given much attention in previous regimes. Besides the Executive’s arduous task of screening nominees thoroughly, the Constitution also gave the Legislature power through the National Assembly’s Committee on Appointments to vet and approve the nominees before they could be sworn in.

Among the 12 nominees presented to the nation from the second list was Professor Jacob Kaimenyi Thuranira for the docket of Education, Science and Technology. He stood calmly beside the President as his qualifications were read out, cutting the image of a man who understood the challenges of the task he was being called upon to undertake. Kaimenyi was introduced as a medical doctor, a dentist who had spent the better part of his career practising locally. He began as an intern dental officer at Kenyatta National Hospital in 1978 before being registered to work as a dentist in all departments.

Between 1982 and 1985, Kaimenyi was the Consultant Periodontologist and Head of Department of Periodontology and Periodontics of the National Dental Unit at Kenyatta National Hospital. His main duties at the time involved administration and training of interns. In August 1983, he was appointed Deputy Officer in charge of the National Dental Unit.

To anyone listening, Kaimenyi might have sounded like the obvious candidate to head the Ministry of Health given his vast experience. So why was he given the Ministry of Education while the Health docket went to James Macharia, a career public accountant? Well, Kaimenyi’s CV revealed another feather in his cap — he was also a scholar and university administrator. Before his nomination to public service, he was the Deputy Vice Chancellor (Academic Affairs) at the University of Nairobi. For more than a decade, he had served in various administrative capacities and was in charge of key educational programmes, including curriculum development and implementation, assessment and evaluation, and human resource management. This work experience must have informed his nomination and subsequent approval by the National Assembly. In his nomination acceptance speech, Kaimenyi vowed to “do whatever is humanly possible to be a team player and (to) deliver”.

At the time, the education sector was just beginning to feel the heat of President Mwai Kibaki’s (President Kenyatta’s predecessor) Free Primary Education policy and the Basic Education Act 2013, which contained radical reforms. With Kibaki’s government taking over the responsibility of paying tuition fees for primary school pupils, the view that education is a right rather than a privilege became more pronounced.

Among the Jubilee Party campaign promises was one to “expand access and raise the standards in education”. Despite a high enrolment rate in primary schools, only 66.9 per cent of students transitioned to secondary school. Uhuru promised to increase the rate of transition to 90 per cent, especially for those in disadvantaged areas. Further, he committed to limit classroom sizes to 40 students as a way of achieving the 1:40 teacher–student ratio.

Among these and other Jubilee promises on education, two in particular became so popular with the Kenyan public that they became key political talking-points. First was the promised return of President Daniel arap Moi’s (Kenya’s second President) free milk for primary school pupils. Part of the Jubilee Party manifesto read, “Provide free milk for every primary school child, which will be sourced from county-based dairy farmer Saccos.” The free milk programme was Jubilee’s solution to malnutrition and food insecurity that kept many learners, especially in the arid and semi-arid regions, away from school. The second promise was to work with international partners to provide solar-powered laptop computers for school children in Kenya.

Once Jubilee Party won the 2013 General Election, the responsibility for implementing the government’s agenda in the education sector fell heavily on the former medic and university administrator, Kaimenyi.

The first task on his table was to implement various acts of Parliament that addressed key reforms in the education sector. The Basic Education Act 2013 was fundamental and Kaimenyi got on it almost immediately. Part 4 of the Act addressed access to education as a right. The Free and Compulsory Basic Education policy summoned key stakeholders — parents, government and teachers — to take up the responsibility of ensuring the right of the child to education was not denied. The Cabinet Secretary’s task was to come up with structures and functions that guaranteed access, quality, equity and relevance.

Specifically, the Act called for the establishment of pre-primary, primary, secondary, mobile and adult schools within reasonable distance in every county. The Act also assigned parents and guardians the legal responsibility of admitting and/or causing the admission of every child in school. Failure to take a child to school became an offence — any parent or guardian who abdicated this legal responsibility risked at least two years in jail or a fine of up to KES 100,000.

But as the government and parents were slowly adjusting, the Act was brewing chaos and resistance among teachers and education sector stakeholders. Just before he exited the Ministry of Education, the late Mutula Kilonzo (the previous office holder under Kibaki) had already faced the wrath of teachers while attempting to introduce legislation that banned extra tuition. At the time, it was the norm for public and private schools to organise paid extra tuition for students in both primary and secondary schools. Under this arrangement, students would remain in school for two or more weeks during the school holidays for extra lessons, which parents were expected to pay for. Kilonzo nonetheless managed to ban holiday tuition and the attendant charges.

The Kenya Secondary School Heads Association (KESSHA), the Kenya National Union of Teachers (KNUT) and the Kenya Union of Post Primary Education Teachers (KUPPET) opposed the ban, arguing that the national education system was examinations-based and, therefore, the extra tuition was in the best interests of students. Kilonzo relented only slightly, saying there was no problem with privately organised extra tuition.

The legal foundation for these reforms was that extra tuition and the fees imposed on it were in contravention of the principles of equity and accessibility. In addition, there was a feeling among those who supported the reforms that schools were stealing from students time they should have been spending with family, where important life skills are best learnt.

Such was the anti-reform environment that Kaimenyi inherited, yet he had even more radical reforms to put on the table. The government also banned all school admission costs, arguing that no child should be denied entry to any public school for lack of admission fees. The Act also banned corporal punishment in schools, which ignited public debate on the state of discipline in schools, especially around 2016 when many school buildings were burnt down by rowdy students. There was a general feeling that the government policies ‘favoured’ the student and were out of sync with the local context and prevailing circumstances. For example, the Act also recommended the inclusion of one member of the students’ council on every school board of management.

Kaimenyi did not back down despite the fierce criticism. Instead he tried a mix of consultative and firm hand approaches to ensure that all the policies were implemented. He even launched a toll free number through the Elimu Yetu Initiative to push for implementation of the policies, in the hope that government could track cases of hiked school fees, organised extra tuition and any form of misappropriation of public resources in schools. “Parents and other education stakeholders and, of course, civil society organisations such as Elimu Yetu Coalition must wake up to call us to account,” Kaimenyi told a meeting of stakeholders at the Kenya Institute of Curriculum Development on 15 October 2015.

However, it was not long before things took a nose dive for the Jubilee administration. Across various sectors, there was vehement opposition from vested interests to the government’s reforms and implementation strategies. The first cohort of professional and apolitical Cabinet secretaries faced a baptism by fire of sorts.

While in Information, Communications and Technology (ICT), Matiang’i had come out as a no-nonsense policy enforcer during the migration from analogue to digital broadcasting, the government was facing accusations of corruption in the Ministry of Lands, then headed by Charity Ngilu who faced the axe over a graft report that the Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission (EACC) presented to the President in 2015.

Ngilu and Najib Balala (the CS for Tourism) were the only exceptions in a Cabinet that did not feature individuals with a history in politics. Both had contested for senatorial positions in their respective counties and lost. While nominating them for public service, the President remarked that they had agreed not to let their political histories get in the way of their professional delivery. The Ministry of Devolution and Planning (headed by Anne Waiguru) was also targeted in the allegations of corruption. Ngilu and Waiguru ended up resigning from government.

It was not long before Kaimenyi’s turn at the guillotine came. His determination to implement policies under the Basic Education Act 2013 and the Basic Education Regulations 2015 met fierce resistance from KESSHA, KNUT and KUPPET and from the Kenya Private Schools Association, who felt they were being over-regulated. In July 2015, the Speaker of the National Assembly approved an impeachment motion moved by Matayos MP Geoffrey Odanga, who alleged that Kaimenyi had acted in contravention of various laws in the education sector. The hot potato issue at the time was the banning of the school ranking system in national examinations.

Odanga, a former teacher, accused the CS of exhibiting arrogance and disrespect during his interactions with key stakeholders in the sector. Kaimenyi survived impeachment by only a slim majority, but he lost his voice within the sector. A delay in the tendering process for the schools laptop project only made things worse.

Earlier, in January of the same year, Kaimenyi had aroused the wrath of teachers’ unions when teachers downed their tools and he responded by saying they were being insensitive to the goodwill directed towards the education sector. In an exclusive interview with KTN, a local television station, the CS maintained that the strike was illegal and added that teachers who had neglected their duties would face the law. Seven months later, the Jubilee government faced another strike that lasted 5 weeks as teachers demanded a 50–60 per cent pay rise. The President himself came out to dismiss their demands, reasoning that agreeing to them would raise the wage bill by more than 10 per cent. As the strike went on, teachers and parents went as far as suggesting the postponement of national exams for that year because students had been out of school for weeks.

Just before the end of 2015, the President opted for a Cabinet reshuffle as the stain of corruption allegations threatened the success of his regime. Although he and his deputy had promised to wipe out the demons of impropriety, at the time it was clear that the country was close to tipping point. As the reshuffle loomed, Kaimenyi’s fate was unclear. However, he was retained and moved to head the Ministry of Lands while the Education docket was handed to the tough-talking Matiang’i, who was deemed a match for the hostile players in the sector.

In Lands, Kaimenyi proved a silent but effective worker who oversaw the implementation of key reforms. During his tenure, he boosted the registration and issuance of 2.4 million title deeds in 1 year, compared to a cumulative 5.6 million title deeds issued by that time since Kenya attained independence. His time in Lands also saw the first tenure of the Jubilee government conducting more land surveys and maintenance of Kenya’s national and international borders. But perhaps his greatest achievement was the digitisation of land records and related services that resulted in the launch of the National Land Information Management System (NLIMS).

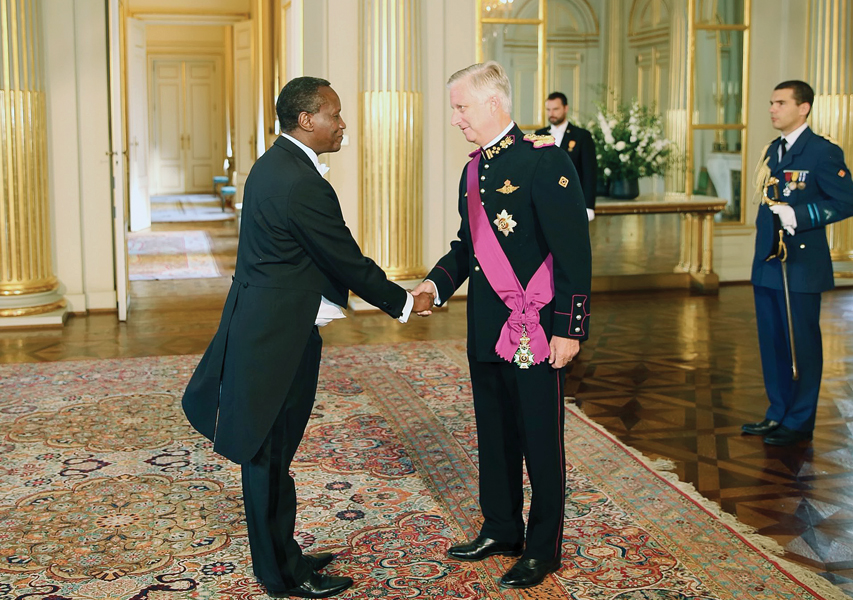

When the President named his second term Cabinet line-up in 2018, Kaimenyi was not among the six cabinet secretaries that were retained. He would later be deployed as the country’s ambassador to Belgium.