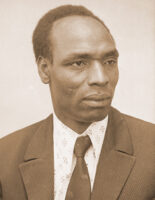

Growing up, James Njagi Njiru’s acquaintance with the world outside of the place where he was born was minimal. But not even dropping out of school after getting his primary certificate could deter him from joining elective politics – he decided to vie for the Kirinyaga West parliamentary seat to become the constituency’s second MP in 1969.

After dropping out of school, Njiru, who was born in Kiaritha Village of Kirinyaga District (present-day Kirinyaga County), became a political activist in his home town and by independence, he had joined the youth wing of the ruling party, the Kenya African National Union (KANU). Owing to his organisational skills and leadership qualities, KANU youths in the district elected him as their leader. His work was to mobilise young people to attend political rallies, chiefs’ meetings and other gatherings the government organised for the community.

Being at the heart of the KANU campaigns in Kirinyaga for the country’s first General Election in 1963, Njiru, then in his early 20s, had carved a niche for himself as an effective youth mobiliser. He vied for the Kirinyaga West parliamentary seat but lost to Njagi Kibuga. However, by the next elections in 1969, his popularity was such that he easily trounced Kibuga.

Njiru’s entry into Parliament gave him his first formal job and he went on to make a name for himself in the country’s political arena. He eventually rose to become a member of President Daniel arap Moi’s inner circle and was appointed the Minister for National Guidance and Political Affairs.

In the early 1970s, Njiru was known for his role in defending the ruling party both in and out of Parliament

As the KANU Kirinyaga Branch Chairman, the MP wielded so much power that he often found himself at odds with people opposed to the party leadership. For instance, soon after his appointment as a minister, he was quick to proscribe Beyond Magazine, a publication sponsored by the National Council of Churches of Kenya (NCCK) and which exposed corruption in the government. Backed by other critics of the KANU regime, NCCK accused Njiru of blatantly abusing his powers by being domineering towards anyone perceived to be anti-Moi.

When Njiru died in June 2013, the Business Daily ran with the headline, “Death of a KANU stalwart and tin god.” Other catchphrases the press used to refer to the minister who had crossed swords with many politicians, the clergy and civil servants included “Kirinyaga KANU strongman” and “Kirinyaga KANU Supremo.”

In the early 1970s, Njiru was known for his role in defending the ruling party both in and out of Parliament. He established a formidable network of KANU youth wingers in Kirinyaga and, with his mastery of the political platform soon caught the attention of party bigwigs, including President Jomo Kenyatta, as he led delegations of party leaders from Kirinyaga to State House Nairobi.

By the time the 1974 General Election was approaching, the young MP had made a name as a leading political player – mainly for his role in party activities such as recruitment drives. He therefore faced no challenges defending his seat, which he again retained in 1979, the year Moi appointed him the Assistant Minister for Health.

Njiru was seen as a leader who was obsessed with power. For instance, he often sought to be recognised as the senior-most politician in Kirinyaga. This would explain why he frequently clashed with his counterpart from Kirinyaga East Constituency (since renamed Gichugu), Nahashon Njuno, during his early years in Parliament. Like Njiru, Njuno, who entered Parliament in 1974, was in the league of youthful MPs.

In his autobiography, Troubled But Not Destroyed, Rev Dr David Gitari, who was the Anglican Bishop of Mt Kenya East Diocese, claimed Njuno narrowly escaped death when his rival attempted to shoot him with a pistol in a bar in Kutus Town, Kirinyaga. The two MPs had disagreed over where the district headquarters should be – the Kirinyaga West MP had opposed his rival’s plans to relocate the headquarters to Kutus.

According to Gitari, Njiru had found his fellow MP having drinks with colleagues and shot at him, but the bullet missed its target. A frightened Njuno and friends ran for dear life in every direction. “The matter was investigated by police but to the best of my knowledge, no action was taken against Njiru,” wrote Gitari.

A more embarrassing incident occurred some time later, when the two leaders had a physical confrontation in Parliament. It was 13 October 1981 and both were assistant ministers – Njiru in health and Njuno in the Ministry of Transport and Communication. The two faced off and even exchanged blows before they were separated by MPs who heard the commotion in the lobby. Njiru ended up in hospital and managed to evoke sympathy from the public when a photograph of him recuperating appeared in the local dailies. He blamed Njuno for ambushing him.

He presented another pitiable picture when he rose to talk about the incident on the floor of the House and claimed that his opponent had, prior to the violent confrontation, planned to attack him with the aim of taking his life. He said he had alerted the police and the House about the threat, which was actualised while he was looking for a file in the members’ private room in Parliament. Njiru said his attacker had unexpectedly hit him with a chair.

“I felt someone hit me very hard with a chair and I fell down. I discovered that my attacker had a small knife and I got hold of his arm,” he was quoted saying by the Hansard. “Thank God that some security people came to my rescue although my attacker managed to run away.” He then disclosed that the attacker was Njuno.

Njuno, on the other hand, went about boasting to the press that Njiru was lucky he (Njuno) had used only his left jab during the fight. Had he used the right, he asserted, Njiru would have been a dead man. The incident elicited sharp reactions from all corners of the country and became the subject of public debate.

Moi, who was barely three years in power at the time, pardoned the two leaders and asked the Minister for Internal Security, G.G. Kariuki, to reconcile them. The President seemed to have a soft spot for Njiru, who had since the early 1970s remained one of his most trusted lieutenants. The pardon was ostensibly meant to help the two MPs save face but the electorate in Kirinyaga West would not forgive Njiru.

The political landscape in central Kenya had also begun to change after the Vice President, Mwai Kibaki, decided to position himself as the region’s kingpin – in the 1983 General Election, he had fielded his preferred parliamentary candidates in almost every constituency in Central Province, including Kirinyaga.

Kibaki had John Matere Keriri compete against Njiru, who found he was no match for the newcomer. Apart from being a member of Kibaki’s camp, Keriri also had a strong academic background. The Makerere University-trained economist who had held senior positions in the civil service was expected to bring change to Kirinyaga.

It turned out to be a double tragedy for Njiru who, besides losing his parliamentary seat, also lost Moi’s favour for being associated with Charles Njonjo, the Minister for Constitutional Affairs. Njonjo had been accused of trying to overthrow Moi’s government. Meanwhile, Njuno had retained his seat, having allied himself with Kibaki.

Two years after the elections, Moi started a campaign to consolidate himself in central Kenya where Kibaki seemed to have taken control. In Kirinyaga, the President rehabilitated Njiru by having him elected as KANU Chairman during the 1985 party elections. Back in action, Njiru was once again the man to watch in the district. With the government’s support, he reactivated his networks after kicking off his campaigns for the 1988 General Election. His plan was to recapture the seat he had lost to Keriri.

Meanwhile, a new voting system had been introduced in which KANU had to conduct nominations first to pick the candidates who would vie for the various constituencies. The party primaries were conducted by having voters queue behind the portrait or photograph of their preferred candidate.

This new system, commonly known as mlolongo (queue), received countrywide condemnation as it was viewed as a means of targeting Kibaki-allied politicians. One of its critics was the NCCK, which described it as a mockery of justice. But Njiru loudly defended it and used it to unseat Keriri. And he did not win alone – his camp comprising Godfrey Karekia Kariithi and Kathigi Kibugi carried the day in Kirinyaga. Kariithi, who was a Chief Secretary in both the Kenyatta and Moi regimes, trounced Njiru’s archrival, Njuno, in Gichugu while Kibugi won in Mwea Constituency.

It was time for the politician many described as a shrewd, audacious go-getter to show his might and win the confidence of the President and KANU once more. Moi knew Njiru’s ability to fight political battles and silence KANU critics, and it was time to reward him by creating a special ministry that came to be loathed even by those close to Moi – the Ministry of National Guidance and Political Affairs.

Together with his Assistant Minister, Shariff Nassir, he once summoned Josephat Karanja, who was by then the Vice President and Minister for Home Affairs and National Heritage, to answer to charges of behaving arrogantly and claiming to be acting as the Head of State whenever his boss was away. The storm had been ignited by another power broker who had denounced an unnamed top politician he alleged was using irregular tactics to set himself up as an overlord of Kiambu politics.

With everyone pointing fingers at the Vice President, the Minister for National Guidance and Political Affairs promised to investigate and subsequently summoned Karanja to confirm or deny the allegations. But Karanja never honoured the summons as the KANU National Chairman, Peter Oloo Aringo, intervened and dismissed the accusations as a Kiambu affair.

In October 1988, Njiru was re-elected the KANU Kirinyaga Branch Chairman, thereby reaffirming his power. Just the mention of his name was enough make top civil servants in the district tremble. Any government employees suspected to be close to ‘enemies’ of the ruling party found themselves in trouble. It was either dismissal or disciplinary action for such individuals.

Meanwhile, Gitari remained one of the strongest critics of the government and the queue voting system. Jointly with NCCK, the clergyman had decided to use every pulpit opportunity to remind people of the mess the elections had created. He wrote in his autobiography that Njiru tried to silence him by mobilising KANU youths to disrupt his church sermons.

“When KANU youth wingers attempted to grab microphones from me as I was preaching at St Thomas’s Cathedral, Kerugoya, in April 1989, I posed the question as to whether this was what was meant by National Guidance and Political Affairs,” he wrote.

Besides the prelate, Njiru had clashed with many other people, starting with his Cabinet colleagues. But to the people of Ndia Constituency and Kirinyaga District at large, he was viewed differently. Known for his generosity, he was a darling of the people.

Through his ministry, he helped several people in his constituency to get government jobs. Whenever his vehicle was spotted in the village, cheering crowds would rush to welcome their MP and demand that he address them. He was known to be cordial and warm hearted when dealing with ordinary people in Kirinyaga, but ruthless when fighting those who he perceived as political foes.

Nevertheless, Njiru was becoming a liability and the time came when Moi made the decision to abolish the Ministry of National Guidance and Political Affairs. This was in 1989, when Njiru’s wars with Gitari had reached a climax. The President had visited Meru District and after addressing a meeting at Kinoru Stadium, he decided to fly back to Nairobi in a military helicopter and allowed Njiru to use his official limousine to get back to Nairobi.

But to the people of Ndia Constituency and Kirinyaga District at large, he was viewed differently. Known for his generosity, he was a darling of the people

On the way, Njiru committed an unforgivable sin. When he got to Wang’uru Township in Mwea, he ordered the presidential motorcade to stop. Why? There was a cheering crowd that demanded to be addressed by the President, or so they thought. Njiru could not resist and decided to address the gathering from the top of the presidential limousine.

This incident angered the President and he summoned Njiru to his office in State House the next day as pressure from other leaders mounted for him to take action against his minister, who was now being accused of plotting to take over the government. Following the coup attempt of 1982 by soldiers from the Kenya Air Force, Moi did not tolerate any threats to his power – real or perceived. The ministry was abolished and the influential minister transferred to the Ministry of Culture and Social Services. Njiru had effectively fallen out of favour with the President.

But his troubles were not over. At home, he was slowly losing his grip as the KANU point man and his camp began to crumble. Kariithi, the MP for Gichugu, had renounced him and joined forces with Njuno after the KANU Kirinyaga Branch, which Njiru chaired, accused him of making secret trips to Uganda to meet with diplomats. Such a move was in breach of trust given his position as an Assistant Minister and prompted the President to sack him.

It later turned out that national security personnel had confused another person with the same name for Kariithi. The rumours returned to haunt Njiru as they had originated from the party branch office. When leaders accused him of being behind them, he found it hard to exonerate himself.

There was also a raid on Gitari’s residence and Moi was forced to order an investigation. At the time, the KANU regime was under scrutiny from human rights organisations and the West for using coercion to silence its critics. Although the outcome of the investigation was not made public, it was said to have implicated the minister.

Njiru was also accused of sabotaging the Kerugoya-Baricho-Kagio road project because it would have ended up benefiting Keriri, his political enemy, as it cut through Kanyeki-ini Ward in Keriri’s home area. The government had allocated money for the project, which the contractor abandoned after laying the foundation. The contractor did not return the money and Njiru was accused of benefiting from it. He vehemently denied the accusations.

It wasn’t long before other political leaders began to disassociate themselves from him. Even Kibugi, the Mwea MP and an ally, left and joined the Kariithi-Njuno group. At one point, Moi went to Kirinyaga to reconcile the rival KANU factions. During his visit, he reinstated Kariithi to the government. And in what appeared to be an indirect warning, the President also cautioned politicians who told lies about others.

After Section 2A of the constitution (which at the time allowed for only one political party) was repealed in 1992, mass defections from KANU to the Opposition started in Kirinyaga, virtually paralysing the ruling party’s operations. It was Kariithi who led the walk-out to join the Forum for the Restoration of Democracy (FORD) led by Jaramogi Oginga Odinga.

Kibaki had also formed the Democratic Party, which was the preferred outfit in parts of Mt Kenya region, including Kirinyaga.

In a bid to salvage KANU, Moi had to call for fresh party elections from the grassroots, and Njiru won. However, he failed to capture the KANU ticket during party nominations and subsequently defected to FORD-Kenya, a faction of the original FORD.

This marked the end of his political career as attempts to make a comeback to mainstream politics also failed. But he did try to mend fences with people whose paths he had crossed and when he died, many eulogised him as a generous and kind-hearted leader.