Friends and Cabinet colleagues of Philip Masinde had a nickname for him — “Permanent Minister” for Labour in President Daniel arap Moi’s regime. Moi reshuffled his cabinets several times and for anyone to serve in the same ministry for the full five-year parliamentary term was remarkable. Masinde was appointed to Labour after the 1992 multiparty General Election.

He headed the ministry during the 1990s, dealing with crises as they arose. Among the major issues he dealt with were the arrest of Joseph Mugalla (the Central Organisation of Trade Unions Secretary General), the billions siphoned from the National Social Security Fund (NSSF) during the 1992 elections, and the crisis over teachers’ salaries on the eve of the 1997 General Election.

The decade coincided with pressure for the reintroduction of multipartism in the country. Some trade unions supported the Opposition’s push for pluralism. But there was another reason for the increase in strikes and industrial strife — the affiliation of the Central Organisation of Trade Unions (COTU) to the ruling party, KANU, was revoked.

COTU had teamed up with KANU in the 1992 election campaigns to ensure that Moi won against a resurgent opposition movement — the only other time this had happened was in 1969 under President Jomo Kenyatta.

Mugalla, the COTU boss, refused to support a call by the Opposition for a general strike to press for multipartism. He argued that this would lead to mass layoffs. But at the Labour Day celebrations on 1 May 1993, in the presence of Masinde, Mugalla called for a general strike to press for a 100 per cent minimum wage increase.

Masinde was representing the President that day — the first time a Kenyan Head of State had missed the celebrations. Workers booed as the minister announced a 17 per cent wage increase instead of the 100 per cent they were demanding. Moi later said the strike was political and declared it illegal. But the industrial action continued for two days, paralysing the country. The government offered to negotiate further increases but through tripartite committees. Mugalla and some union officials were later arrested and charged with inciting workers against the government. However, they were released when the government realised the officials had no case to answer.

Masinde reportedly set in motion the process to replace Mugalla with COTU’s deputy secretary general even though the law required the President to appoint COTU officials after elections. Mugalla took the case all the way up to the Court of Appeal and was reinstated. During the subsequent labour negotiations between the government, unions and employers, Masinde was present.

When he was appointed Minister of Labour, Masinde inherited the crisis involving billions lost at NSSF and, to a lesser scale, the National Hospital Insurance Fund (NHIF). He and his National Treasury counterpart had to deal urgently with the matter. Reportedly, the KANU government had used the money from these institutions to fund the elections in 1992. Several banks, including Postbank Credit Finance, were used to deposit funds taken from NSSF.

The NSSF was allegedly prevailed upon to go into real estate development in Mountain View, Kitisuru and Syokimau — a business far removed from its core business of safeguarding workers’ pensions. The land that NSSF bought was reportedly owned by the government, but had been allocated to influential KANU members. Consultancy and legal fees were also reportedly paid by NSSF to firms set up to access the funds for the campaigns.

Whatever the case, it emerged that worker’s pension payments had fallen into arrears. To try and contain the situation, Masinde changed the NSSF Board and the Managing Trustee, and the incomplete housing developments were seized by NSSF.

A tenant purchase scheme was put in place to try and recover workers’ money. The scheme was extended to Mountain View, Kitisuru and Syokimau, where the developments had stalled at various stages. Empty plots were also sold. The scheme became popular as it gave first priority to NSSF and NHIF employees to own property.

For the bigger banks that had also received NSSF funds, like the National Bank of Kenya, these deposits were later converted into equity, with NSSF as a leading shareholder. These measures helped to sort out and secure the NSSF funds.

Then in 1997, there was the teachers’ strike. The Kenya National Union of Teachers (KNUT) under Secretary General Ambrose Adongo called for a nationwide strike beginning 1 October 1997, barely two months before the next General Election. With national examinations for primary and secondary schools about to start, 260,000 teachers going on strike promised to be disastrous. Masinde and the Minister for Education, Joseph Kamotho, began negotiating with KNUT officials and both sides eventually reached an agreement for teachers to be awarded between 150 per cent and 200 per cent salary increments that would be spread over the next five years ending in 2002, the next election year. This was a huge increase, but there was much at stake. Adongo called off the strike after 12 days.

The ramifications of that hasty decision would affect subsequent governments under Presidents Mwai Kibaki and Uhuru Kenyatta. Successive governments have failed to honour the agreement, resulting in regular strike threats. This situation has yet to be resolved.

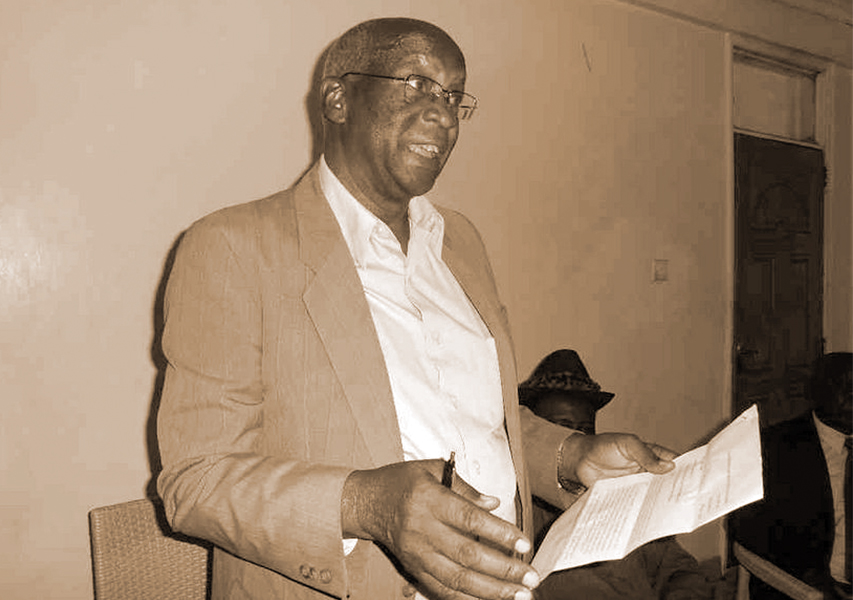

Masinde lost his KANU nomination and parliamentary seat to Chris Okemo in the 1997 elections. A non-controversial politician and Nambale MP for two terms, he will be remembered as an amiable Labour minister who dealt effectively with the crises he faced in office.

The former minister was born in 1933 in Nambale town, Busia District (now Busia County), and had a staunch Catholic upbringing. He worked as a teacher at various intermediate schools in western Kenya before independence. Soon after he got married, he won a scholarship from the Catholic Church to study in the Netherlands.

He earned a degree in political and social sciences and returned home at independence. He became a labour officer and then moved to the East African Airways as a human resource manager.