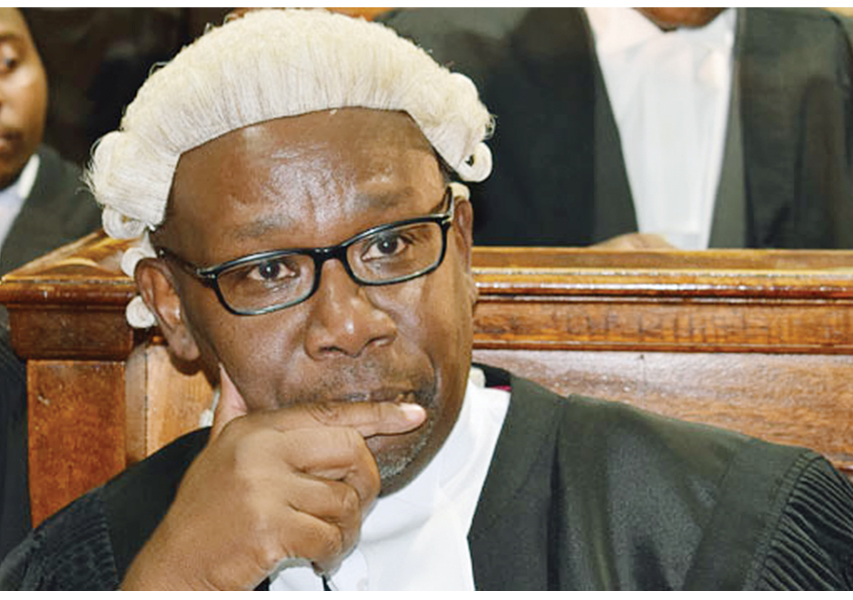

Professor Githu Muigai’s career peaked when he served as chief legal advisor to Presidents Mwai Kibaki and Uhuru Kenyatta as they drafted the 2010 constitution. With the exception of the recently deceased Charles Njonjo, who was profiled in an earlier volume of this series, there has not been a more significant Attorney General since Sir Eric Griffith-Jones.

Born on the eve of independence in Nairobi on 31 January 1960, he completed his Certificate of Primary Education (CPE) at St James’ primary school in 1973, followed by his Certificate of Secondary Education at Gĩthĩga School in Gĩthũngũri in 1977. He then left Kiambu District for Meru School, where he finished first in his class in the A-level exams in 1979.

Githu enrolled in the law faculty at the University of Nairobi in 1980. The post-independence boom in public education had not yet run its course; the faculty was brimming with talent. Dr. Willy Mutunga, who had taught him at the university and whose tenure as Chief Justice partly coincided with his as Attorney General, was his guest at the launch of his full history of Kenyan constitution-making forty-two years later.

The young man enrolled at the University of Nairobi, where he was first in his class in his first year and in 1984, his last. He had his first academic publication (“Intervention in International Law: the Case of Grenada” in the University of Nairobi Law Journal, 1984) within two years of graduation.

Since then, Professor Muigai’s career has been somewhat unusual. Attorneys General were typically appointed after years of public service in state legal offices. He came from private practice with his firm, Mohammed Muigai; from international public service as the UN Special Rapporteur on racism and other forms of intolerance between August 2008 and September 2011; from advising on constitution-making and reconciliation, most notably in Somalia between 2002 and 2004; from service as a judge of the African Court of Human and Peoples Rights; and from a career in academia, perhaps best known for his courses in public policy.

Given that variety, it is worth noticing that two aspects of his career have remained constant. The first is a close attention to the historical circumstances in which law, constitutions in particular, are made; the second an equally close attention to the nature and function of constitutions themselves.

The second first. Professor Muigai’s “Political Jurisprudence or Neutral Principles?” is a telling statement of the problem he sought to solve. East African Law Journal, pp. 1–19, 2004. On the one hand, Kenyan jurists frequently considered their understanding and application of the law to be either apolitical or counter-political; on the other hand, the fruit of their jurisprudence was weighed on inextricably political scales. According to Professor Muigai, Kenyan constitutional interpretation would remain weak outside the courtroom or classroom, unless Kenyan jurists developed a theory of the purpose of the constitution and its interpretation that reconciled the unavoidably political nature of constitutional outcomes with the esoterica of their profession.

The jockeying between the executive and the judiciary after the introduction of the constitution of 2010 vindicated his analysis; the judiciary showed itself not just a political actor, as he had foreseen, but an able one.

In keeping with his conviction that politics mattered, he had long been attentive to the concrete political circumstances in which law is made and which it makes. As previously stated, this interest recently culminated in the publication of the first full-scale history of constitution-making in Kenya, from colonial times to the 2010 constitution. Though that is his most recent published work on the subject, his fascination and familiarity with it dates back to his early career. That respectful familiarity with the history of constitution-making served him well when he was asked to advise on the constitution-making process, which had begun during President Moi’s last term, and then when it came time to oversee its implementation after 2010.

It is time to review both.

The late 1990s and early 2000s constitution-making was fractious: in 1996, the opposition, from which pressure for constitutional reform came, was deeply divided on the issue, with half committed to an election boycott if the constitution was not reformed before the 1997 general election — indeed, at one point, FORD-Asili’s leader ordered his supporters to burn their voters’ cards if the government did not meet his demand for a package of minimum reforms — and another completely committed to the election would. Still, we were on the verge of a constitutional crisis once the reformists decided to change not just government but the rules by which it governed, and once President Moi’s administration realised both that it had to change — a lesson learned from the unrest of 1997 and 1998 — and that the reformists were sufficiently internally divided and open to compromise, that change did not imply defeat.

Professor Muigai was one of those appointed to the Constitution of Kenya Review Commission (CKRC) in 2000, where he worked alongside Professor Hastings Okoth-Ogendo, the Commission’s second vice-Chair, whom he had admired since sitting in his classes at the University of Nairobi, and whom he later referred to as a “wizard of the law.” Although, as is frequently forgotten, the CKRC did complete and publish a new constitution in October 2002, President Moi’s government abruptly halted the constitution-making process to fight the election, which was only three months away at the time, under familiar rules. After that, the Commission reconvened, this time with the goal of putting together a constitution in a hundred days, as envisioned by the new Kibaki administration.

The process was hampered by disagreement once the political stakes became clear. The Constitutional Conference convened in April 2003, but it was adjourned three times that year (once in August 2003 due to the death of Vice President Michael Kijana Wamalwa), dragged into March 2004, and eventually produced the 2005 draft constitution, which was defeated decisively in the November referendum. Even the package of minor reforms proposed just before the election in 2007 failed to pass. President Moi’s decision not to amend the constitution so close to a general election proved prudent.

The disastrous post-election events of 2007-8 reignited the constitutional-making process, in which Professor Muigai had now been involved for nearly a decade. His expertise was once again required. This time, with a narrower mandate and a political class shaken by the consequences of its failure, a new constitution was hammered out and ratified in an August 2010 referendum. From 2001 to 2010, Professor Muigai’s close attention to the history of constitution-making and appreciation for the importance of politics were felt at every stage of the process. He had reason to believe that he had made a lasting contribution to the country’s just governance.

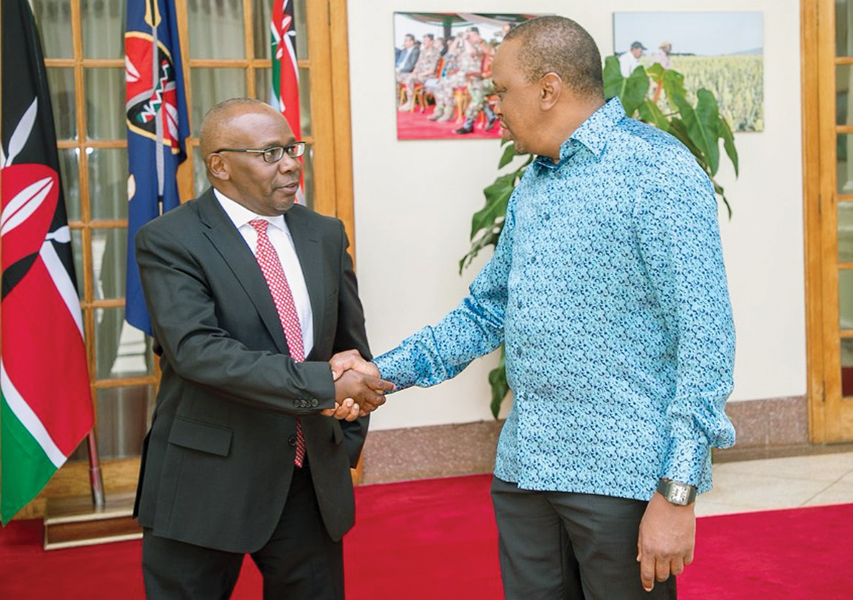

President Kibaki appointed him Attorney General in August 2011, recognising that his previous distinction in public service and familiarity with the constitution he had brought to birth made him the natural choice for the position. His constitutional journey was far from over.

His tenure lasted until 2018, when he resigned to return to private practice and write a history of Kenyan constitution making. It was filled with significant decisions, significant reversals, and astute legal advice, given not only to the Executive, but also to the Kenyan people. A good way to understand his time in office was to notice that he enjoyed the business of teaching—of talking his way through some legal point—and then to see that especially after 2013 he came to regard Kenyans as the sort of attentive (if occasionally wayward) listeners who would benefit from clear (if schoolmasterly) talk about the law.

There were perhaps three particularly important matters awaiting him at his appointment on August 27, 2011.

The first was the International Criminal Court (ICC), which had opened investigations in Kenya following the violence of 2007-8 and had indicted six suspects on March 8, 2011. Given the complex and unprecedented issues raised by the ICC’s intervention, the Kibaki administration would need to understand how to meet its international obligations while also protecting the republic’s sovereignty. The second was the constitution: having ratified it the year before, the country expected that legal preparations for its coming into force would be complete in time for the next election. Indeed, the constitution was a campaign issue in 2013, as it had been in 2002, but Kenyans wanted more than just a new set of rules; they wanted a government and an administrative class that followed them. The demand for a new constitution coincided with the demand for the rule of law. The third of his major issues was corruption: large sums of public money had been stolen or squandered. He was expected to recover losses and make life more difficult for those who might try again in the future.

Rather than review every important decision of his tenure, it might be better simply to recall his part in some of the most consequential.

When the Security Amendment Act of 2014 was passed, the government was widely and loudly accused of acting illegally or unconstitutionally. Professor Muigai made it clear that critics of the law — which had, after all, passed Parliament — would have to wait for the judiciary to rule on what was and wasn’t unconstitutional. That calm confidence in the law and in the country’s institutions and decisions, as well as the implicit assurance that the Executive he advised would accept the court’s judgment of its own conduct, demonstrated the depth of our maturity as a constitutional republic..

So, too, was the Executive’s acceptance of the verdicts in the petitions in the 2017 presidential elections, in which he played a key role as both actor (a respondent in both sets of petitions) and explainer of the constitution to Kenyans and the Executive.

His adherence to an educated reading of the letter of the law was demonstrated by argument in the 2013 electoral petition as amicus curiae that the standard justifying a court’s annulment of an election was the Elections Act: there had to be illegality or irregularity, and it had to be demonstrated that it influenced the outcome. He was later chastised for it, but this position made good sense of the relevant legal language and had the advantage of being consistent with common sense. However, it was thought at the time to be an example of the barren, pedantic jurisprudence against which the new constitution was written. Only later, when it became clear that the standard did not preclude the annulment of irregular elections, did it become clear that his critics had read their desired outcome into the letter of the law when they could have had it anyway.

He was not as successful in dealing with the challenge of corruption. He did not have the broad formal powers of prosecution that his predecessors had, and he had taken office at a time when the course of the larger corruption cases had been set, and his advice could change little. The nadir, perhaps, was President Uhuru Kenyatta’s announcement on May 16, 2014, that the Anglo-Leasing debt, though incurred illegally, would be paid, both because the government had already lost cases in relation to the debt and because his administration’s Eurobond issue would fail otherwise.

There have been other successes. When excited talk of a parallel swearing-in spread after the election in December 2017, he retorted that any attempt to swear in anyone who had not been lawfully elected as President would be treasonous. Given the gravity of the situation, the language was strong. Though his role as an explainer required him to speak plainly at times, he was also a persuasive speaker with a knack for the memorable phrase (“I am a mortician …”; “ … ignorance has never stopped a Kenyan giving his opinion …”) and so well suited for this latter role.

He played it well, perhaps never better than at the ICC hearing in October 2014, when he described Kenya’s efforts to cooperate with the ICC’s requests under two Prosecutors, through two administrations. It provided a rare glimpse into the pressures of the office: he was among those primarily responsible for honouring the country’s foreign obligations while also defending the republic’s sovereignty and constitution. He threaded the needle by demonstrating what Kenya had done to meet the prosecutors’ requests, while insisting that it retained the capacity to try serious crime suspects.

He left office shortly after the 2017 election, with the constitution firmly in place, a contested election settled, and enough time for his successor to settle before the next election. On February 13, 2018, President Uhuru Kenyatta accepted his resignation and announced that he would name Justice Paul Kihara Kariuki, President of the Court of Appeal, as his successor. Justice Kariuki was sworn in on April 28, 2018, the day after the National Assembly approved his nomination as independent Kenya’s seventh Attorney General.

Professor Muigai, now retired from public service and the author of a history of constitution-making in Kenya, can look back on a distinguished career at a critical juncture in the country’s history: nearly two decades in which he was involved, on and off, in the business of both making and establishing the constitution of what amounts to a second Republic.