On 12 February 2020, President Uhuru Kenyatta’s Cabinet Secretary without portfolio, Raphael Tuju, almost died – again. He was strapped in and fast asleep in the front passenger seat of his official vehicle on this cold, wet early morning as his driver cruised towards Nakuru County, where the CS was expected to join the President and fellow Cabinet secretaries for the funeral of Kenya’s second President, Daniel arap Moi.

In Kijabe, barely 60 kilometres out of Nairobi, a matatu with its headlights on full beam came hurtling round a bend on the wrong side of the road and collided head-on with Tuju’s vehicle. Cabinet Secretary Amina Mohamed (Sports, Heritage and Culture), whose car was trailing Tuju’s, was among the first responders. She kept him conscious by talking to him while he was evacuated from the accident scene into an ambulance to the nearby Kijabe Mission Hospital.

Senior government officials present at the hospital demanded that Tuju be immediately airlifted to Nairobi for treatment, but the doctors would have none of it. They insisted that their patient required immediate surgery without which he was unlikely to survive the helicopter dash to a better equipped facility in Nairobi.

By putting their foot down, a trait shared with their famous patient, the surgeons led by Dr. Peter Bird, an Australian missionary, saved his life. Besides 18 fractured bones, one of Tuju’s broken ribs had pierced and collapsed his right lung, causing heavy internal bleeding and laboured breathing. It was a close call. Tuju spent eight days at the Karen Hospital Intensive Care Unit before being flown to the United Kingdom for specialised treatment on the President’s personal intervention. It would take two to three months for him to heal, his doctors said.

This was not Tuju’s first brush with death. Seventeen years earlier, on 22 January 2003, a 24-seater plane carrying senior members of newly elected President Mwai Kibaki’s Cabinet crashed into a house after hitting a power line on take-off from Busia in western Kenya. Minister for Labour Ahmad Mohammed Khalif died shortly after being admitted to a nearby hospital. Tuju, the Minister for Tourism, Linah Kilimo, Minister of State in the Office of the President, and Martha Karua, Minister for Water, were airlifted to Nairobi in critical condition.

It would take months of intensive physiotherapy following the Kijabe crash for Tuju’s broken limbs to heal so he could walk again. That he was able to stage a 52-kilometre charity walk after his recovery in aid of the hospital that saved his life is testimony to the stubborn spirit that has defined the life and times of a man born into poverty and who raised himself by the bootstraps to the rarefied world of wealth, influence and political power.

Unlike many whose poverty in their formative years remains permanently etched on their faces despite any wealth and power they manage to acquire later in life, Tuju could easily be mistaken for one who was born with a silver spoon in his mouth. Suave, gentlemanly, well spoken – even posh, he always came across as a man more at ease in boardrooms than at a Kenyan political rally. But make no mistake, this man with a taste for the finer things in life had a reputation for being a political brawler of repute.

Born on 20 March 1959 to Mama Mary and Mzee Henry Odiyo Tuju, he was your typical rural child who nonetheless was slightly more privileged to experience the pulse of Kenya as he moved from station to station when his father worked for East African Harbours and Railways.

When his mother died in 2011, Tuju explained that she had fallen sick when he was born, and that he was breastfed by her co-wife (his stepmother) who had just lost a baby. It was his mother, who incidentally wanted him to be a priest, and whom he accompanied to the market where she sold wares from the time he was nine years old, that he credited for his business acumen.

“She taught me coping mechanisms. She taught me wealth creation at a tender age. She never depended on anyone,” he said.

After his primary school education at Majiwa and Nakuru West schools, Tuju joined Starehe Boys Centre and School in Nairobi, the national school famed for admitting needy but brilliant boys. Bright, paying students – often the sons of prominent people — were also admitted. This cocktail of rich and poor offered young, humble Tuju a better glimpse into the world he would straddle as an adult.

It was at Starehe that Tuju first wore underwear, a gift from the school founder, Dr. Geoffrey William Griffin.

“I never wore inner wear until I came to Starehe. I came here bare … I was a miserable, poor little boy and my first inner wear was given to me by Dr. Griffin. I’ll never ever underestimate the contribution that Starehe Boys has made in my life,” Tuju said during the school’s 60th anniversary celebrations.

One might say it was also at Starehe, an institution that prides itself as a centre of excellence, that Tuju became a refined, cultured go-getter, no doubt inspired by the school motto, ‘Natulenge Juu’ (Let Us Aim High). He also seems to have carried with him an empathy for the poor; one he would later demonstrate as a Member of Parliament.

After school, a career in broadcast journalism beckoned and he became a household name and national celebrity, first at the Kenya Broadcasting Corporation (KBC) and later as a pioneer news anchor with the Kenya Television Network (KTN). But it was the HIV and AIDS pandemic that saw Tuju become a millionaire entrepreneur with interests in media, communications, hotels and real estate, and set him on the path to politics.

He was later to go to the University of Leicester where he obtained a Master of Arts degree Mass Communication that anchored his credentials as a leading communication consultant both locally and internationally. Unbeknownst to Kenyans, Tuju is a respected communication expert whose consultancy practice, especially for international clientele until today, pays him more money than his Cabinet salary. That is besides being a director to businesses in the hospitality and real estate sectors.

Noting the miscommunication that led to a numbing fear of HIV and Aids among many as well as stigmatisation of the affected and afflicted, Tuju launched ACE Communications to demystify what was then known as a ‘killer disease’. Besides consulting for the World Health Organisation, the UK’s Department for International Development and the United Nations Development Programme, ACE Communications made history by becoming the first Kenyan media company to win the prestigious Emmy Award – one of four major American awards for performing arts and entertainment. The Emmy was for a UNICEF 2001 ‘Say Yes for the Children’ campaign video featuring his Talia Oyando and his twin daughters.

Having not only set the bar but also scaled the peak of his journalistic career, Tuju, like most gifted individuals, would require a new challenge. So it was no surprise when he ran for the Rarieda parliamentary seat the following year via Raila Odinga’s Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), which was part of the National Rainbow Coalition (NARC), and won. He was a breath of fresh air — youthful, dapper, eloquent and wealthy, with impressive organisational, oratory and campaign skills. What’s more, he enjoyed national recognition on account of his many years on television. Keen political observers were of the mind that his eyes appeared set beyond his backwater Rarieda Constituency; it was an observation that would set Tuju against Raila in years to come.

Upon his election, he was appointed Minister for Information and Communication, and Minister for Tourism and Wildlife between 2003 and 2005. He is credited with wresting the iconic Kenyatta International Conference Centre, which had been illegally appropriated by the Kenya African National Union, the ruling party of a past era, and bestowing its ownership back to the public. He also received praise for enabling the proliferation of privately-owned radio and TV stations, and the broadcasting of more local content, a directive that created employment for hundreds of Kenyan artistes.

Meanwhile, Tuju was tapping his international networks to secure funding for development projects in his constituency. His areas of focus were health, water, electricity, schools, women groups and AIDS orphans. A mobile health clinic funded by an Italian philanthropist and unveiled by President Kibaki particularly captured national attention because of its ingenuity.

Ironically, these efforts — launching water projects, roads, fish refrigeration facilities at landing sites, introducing ferry services between Uyoma, Karachuonyo, Asembo Bay and Mbita in Suba District — and his apparent quest to make Rarieda a model constituency, were raising eyebrows within Nyanza region. Was he trying to upstage Raila or position himself as the next Luo leader? It didn’t help that NARC had turned out to be a quarrelsome and divided coalition, with one faction led by Kibaki and the other by Raila.

When over half the country voted against the 2005 constitutional referendum in a heated charge led by Raila, President Kibaki dissolved his Cabinet. Tuju, who had not only switched allegiance from LDP and Raila to Kibaki, but had also supported the referendum opposed by his party and party leader, was appointed to the powerful Ministry of Foreign Affairs in the new Cabinet. The Luo community was livid. No Luo politician had so far dared take on Raila without meeting their Waterloo at the polls, and Tuju was no exception. His development record notwithstanding, he was beaten hands down in 2007 when he vied to defend his seat via his People’s Progressive Party (PPP).

But Tuju did not sink into political oblivion. Kibaki named him Special Envoy and Presidential Advisor on Media and Management of Diversity of Ethic Relations, a position he held until 2011, when he resigned to form the Party of Action (POA) and announced his intention to run for President in 2013. The announcement elicited vicious trolls on social media platforms from members of the Luo community. His own Rarieda constituents, for whose interests he had championed as MP between 2002 and 2007, yet who had never forgiven him for ‘abandoning Raila’ in 2005, scornfully chided him to take his ‘maendeleo (progressive) projects’ away.

Not that the math added up for a Tuju presidency anyway. Uhuru was firmly in the saddle, with his Central Kenya and Rift Valley political bases intact. Raila, on the other hand, had a firm handle on his traditional Nyanza, Western and Coast bases. A Tuju run wouldn’t have registered a wee toot on the political Richter scale; after scanning the landscape, he wisely chose not to run for President.

Still, the people in his village assigned his mother, driver and a relative the three votes Uhuru got at the local polling station. Like her son, she became a pariah. By his own admission, she was unable to visit his magnificent rural home due to the local hostility. He however said this never affected his relationship with Raila, with whom he later reconciled and teamed up in the run-up to the 2022 General Election.

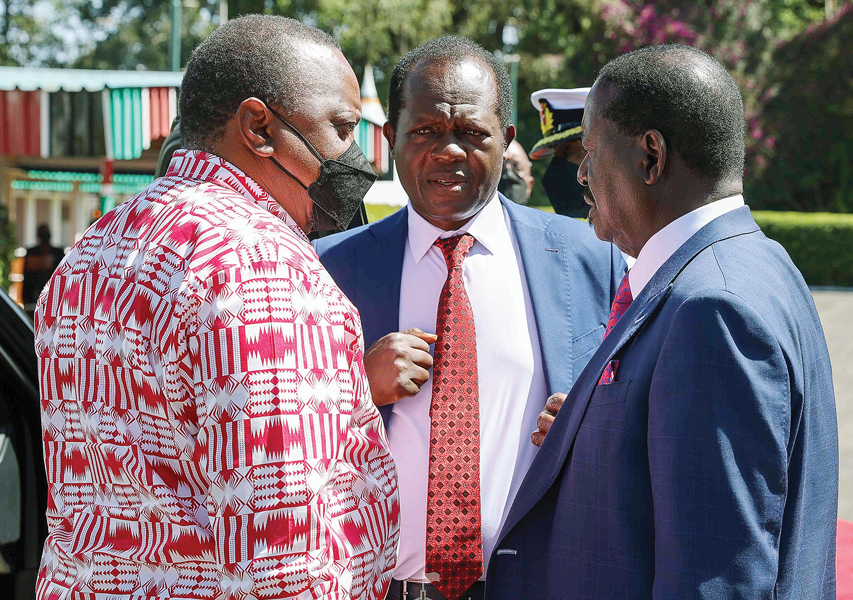

“My late mother, who was born in Sakwa (where the Odingas come from), always reminded me that I might differ with Raila in politics but I must never disrespect him as he is my uncle,” he explained after her death. After the 2013 election, Tuju immersed himself in his private businesses until 2017, when he reemerged as Secretary General for Jubilee Party, which was Uhuru’s campaign vehicle for the 2017 presidential race. It was a vantage perch, one that allowed him to exploit his leadership, professional, political and managerial skills while at the same time helping him become the senior-most Luo politician with the closest access to the Jubilee presidential candidate. When Uhuru won, it was widely expected that Tuju would be allocated a senior Cabinet position to represent the Luo community in government. Instead, Uhuru appointed him Cabinet Secretary without portfolio, a position that Presidents Jomo Kenyatta and Daniel arap Moi often used to reward party loyalists.

Why would a man with Tuju’s gifts be treated thus despite the obvious friendship he shared with Uhuru? Besides flying the ministerial flag on his official vehicle, how did he spend his working day?

What Kenyans didn’t realise was that Tuju’s ‘without portfolio’ docket actually came with a truckload of portfolio and that behind the scenes, he wielded great influence in Uhuru’s government. With a brief to coordinate the implementation of the 2017 Jubilee manifesto, which was anchored on the pillars of Transforming Lives, Transforming Society and Transforming the Nation, his tentacles spread across ministries, making him, in football terms, Team Uhuru’s political box-to-box midfielder.

It was a fitting choice. Tuju, diplomatic but firm — stubborn even — had the confident air of a man accustomed to order and getting things done. Tuju’s hidden hand also lay in the Big Four Agenda legacy projects that were implemented at dizzying speeds during Uhuru’s second term.

As Uhuru’s presidency drew to a close, Tuju was among several Cabinet secretaries who resigned, first as the Jubilee Secretary General and later as CS, fuelling speculation that he was pursuing an electoral seat as either a governor or a senator. Having reconciled with Raila, such a move would have been warmly received by voters in Siaya County.

“I am a political animal. I have been a politician since I was elected MP for Rarieda. I now want to go back to the people and seek their mandate. I will not say which position I’m going for because as a political animal, I don’t want to alert my political foes when I will strike,” he announced when he resigned from Jubilee. In the end, he took up the position of Executive Director of Azimio la Umoja (Raila’s newest campaign vehicle), which essentially meant taking charge of efforts to ensure that Uhuru’s preferred successor (Raila) became the fifth President of Kenya.

james oduol says:

This is a very informative,well written account of the man Hon Raphael Tuju.He actually looks younger than his age at 64 years.Your article has revealed his year of birth which i had wrongly assumed to be 1960s.