Smallholder Scheme in the Rift Valley on

October 4,1962.

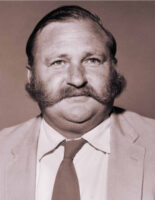

Roy Bruce McKenzie earned the distinction of being the only minister in the colonial government who retained his position upon Independence and held the portfolio until 1969, when he resigned on health grounds. He was the Minister for Agriculture.

The South African-born politician is credited with steering Kenya’s agricultural economy through its worst period as white-owned farms were transferred to African owners and large-scale agriculture was replaced with small-scale farming.

Born in 1919 to Roy Douglas McKenzie, he completed early education at Hilton College, a private boarding school for boys in the KwaZulu-Natal Midlands. McKenzie joined the South African Air Force (SAAF) in 1939 when World War II broke out and later fought as part of the SAAF squadrons deployed to fight Mussolini’s war in Africa. For that, he received two distinguished medals: the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) and the Distinguished Service Order (DSO).

McKenzie was one of the soldiers demobilised after the war in 1946. He migrated to Kenya and settled on a 1,200-acre dairy farm in Solai, Nakuru, which he named Gingalili Farm. He reared some of the best pedigree cattle in the country and white farmers for many years elected him chairman of Royal Agricultural Society of Kenya, now the Agricultural Society of Kenya.

As one of the most successful colonial farmers, McKenzie joined the league of farmer-politicians, who included leading protagonists Michael Blundell, Ferdinard Cavendish-Bentinck (CB) and Charles Makham, to lead settler politics in Kenya. In 1957, McKenzie was nominated to the Legislative Council (Legco). He was present at Government House, Nairobi, when British Secretary of State for the Colonies Allan Lennox-Boyd told Legco that he would impose a Constitution on Kenya which would last for 10 years.

But McKenzie was not a keen supporter of a lengthy constitutional handover that white settlers, keen to get capital out of their investments, favoured. The Lennox-Boyd Constitution, which provided for 14 Africans, 14 Europeans, six Asians and two Arabs in the Legco faced handicaps during the 1958 Legco opening.

The 14 elected Africans walked out on Governor Evelyn Baring after he announced that there would be no further constitutional changes. This led to a standoff. Musa Amalemba was the only African to accept a ministerial post.

It was in a moment of anger that Blundell stepped down as Minister for Agriculture, Animal Husbandry and Water Resources to form the New Kenya Party to advance his moderate political beliefs. His fellow liberal colleague McKenzie took his place in 1959 — a move meant to assure the white settlers that they had nothing to fear. Blundell’s earlier attempts — in April 1959 — to have Africans join his New Kenya Party was rejected for the African leaders wanted to engage the colonial government in constitutional talks and did not want the Lennox-Boyd one.

McKenzie joined the government when Harold Mcmillan took over as British Prime Minister and declared that “a wind of change” was blowing in the colonies. It was also an interesting period in Kenyan politics: Ian MacLeod had replaced Lennox-Boyd as Secretary of State for the Colonies and announced the end of the Lennox-Boyd Constitution. As a result, African legislators ended their boycott of the Legco.

McKenzie took over at the Ministry of Agriculture when white settlers had panicked at the prospect of an African-led government. It was through McKenzie that the thorny land question was to be settled. In London, during the Lancaster Conference, he was asked to come up with a policy that would satisfy Africans and Europeans. Through his efforts and negotiations with MacLeod, the willing-buyer willing-seller policy was floated.

As the Minister for Agriculture, McKenzie was one of the most unpopular figures among white farmers and was often eclipsed by rightwing radicals. These included former Legco Speaker Ferdinard Cavedish-Bentinck, who led a spirited campaign to have Britain compensate the farmers for any loss.

It was McKenzie who first informed an April, 1960, settlers’ meeting at County Hall, Nairobi, that the Government would buy the large farms and sub-divide them among the new African farmers and the whites would act as supervisors. The hall burst out in laughter!

It was through his efforts that the resettlement of Africans in the highlands was mooted and formulated. McKenzie had an able supporter in Blundell, the man he replaced at the ministry. In the Legco, McKenzie had warned that if there was a “rat race” exit of European farmers from Kenya after the promised 30 million pounds for purchase of land was made available, it would be impossible to hold the national economy. Because of these fears, MacLeod held a meeting with Gichuru and Mboya, in September, 1960. McKenzie later met Local Government Minister Wilfrid Havelock and McKenzie and assured the two that there would be no troubled exit for white farmers and that he would press the British government to give the new Kenya government money to resettle landless Africans, especially in the so-called White Highlands.

McKenzie — and, to some extent, Havelock — had emerged as the most moderate white ministers representing Blundell’s New Kenya Group. The group was closer to Kanu than previously thought. From the onset, therefore, McKenzie was part of a group aiming at a multi-racial Kenya. He hoped that this could help eliminate the colour problem before Kenya became independent. But it was the recession caused by a drop in agricultural production and settlers’ panic that worried him in the run-up to the release of Jomo Kenyatta.

At most forums, he preached responsible leadership and dismissed talk of an economic collapse if the Africans took over. He hoped the new leadership would not act irresponsibly, especially on the land issue. But McKenzie faced political problems for his efforts.

On October 7, 1960, the European Convention of Associations on a 38-4 vote supported their executive committee’s decision to back Cavendish-Bentick and his Kenya Coalition at the elections, a move meant to eclipse McKenzie’s New Kenya Group. In the scenario, moderates like McKenzie would have no place in European politics. As a result, he slowly shifted his sympathies to Kanu, which was emerging as the most popular African party.

The white farmers were worried that if McKenzie and his ilk, including Blundell, had their way, Europeans would be represented at the second Lancaster Conference on Kenya’s independence by a group largely representing the thinking of Tory backbenchers at Westminister – and that was supported by the British government.

Occasionally, McKenzie would shift the fight to London and accuse Cavendish-Bentick’s Kenya Coalition of seeking privileges for the minorities, spreading alarm and despondency, scaring money away from Kenya, and advocating a “scuttle policy”. But Cavendish-Bentick claimed that the New Kenya Party was allied to the British government, giving this as the reason why members did not oppose it.

When Kanu won the 1961 elections, but refused to form a government until Kenyatta was released, McKenzie also refused to join the coalition government, arguing that it would not serve the long-term interests of the minority. Interestingly, he joined Kanu and worked alongside Gichuru and the last Governor, Malcolm McDonald. McKenzie thus gave Kanu the support it required as it pushed for a unitary state and its willing-buyer, willing-seller proposals on land, which reflected the thinking in London. He was against Kadu’s Majimbo system of government and its policy on land. That was how McKenzie managed to straddle the last stretch of colonial politics with ease.

At the Lancaster talks, he became instrumental in persuading the World Bank to fund the land transfers. By bringing the World Bank into the picture, the British government — and, to some extent, McKenzie — managed to achieve two things: Leave Kenya with an obligation to pay for the white-owned land and avert free transfer of land back to the indegenes.

It is now generally accepted that independent Kenya did not break with the colonial economy: it merely Africanised the colonial administrative structures. Britain’s metropolitan corporate interests were safeguarded and a new black-skinned propertied class replaced the white settlers.

It was McKenzie who convinced Kanu leaders to accept the Majimbo Constitution of 1963 to save the Lancaster talks and then throw it away when they get power. In 1963, McKenzie became a specially elected member of the House of Representatives and joined Kenyatta’s first Cabinet as Minister for Agriculture.

In his letters, Kenya’s Governor-General Malcolm MacDonald (1963-1964) continued to press London to support McKenzie’s policies of shaping the new Kenya, especially on land ownership and agriculture. It was McKenzie who organised the August 12 ,1963, Kenyatta-settlers meeting at the Nakuru County Hall, where the Kanu leader issued the “forgive and forget” call and asked the white farmers to stay on.

That evening, McKenzie also organised, with the Kenya National Farmers Union, a cocktail party at Nakuru’s Stag’s Head Hotel for Kenyatta and Gichuru. They then drove to Gingalili Farm to spend the night. That was how close McKenzie was to the new powers. Despite the broad objectives articulated on land settlement schemes, the landless did not fully feel the benefits, the main beneficiaries being the political elite who abused the entire process. On the one hand, it was one of the mistakes that McKenzie made in his political career, but, on the other, he became a darling of the ruling propertied class. It was McKenzie’s efforts that determined whether the British, who had exclusively monoplised coffee, sugar and cotton plantations, would remain after Kenyatta gave the passport-holders two years to decide whether they wanted to become citizens.

McKenzie faced a myriad of problems at the ministry. He was to work with the Ministry of Lands and Settlement to achieve his targets, but lack of livestock meant that the dairy industry would not take off as expected. But he increased the acreage under coffee produced by African small-scale holders and an additional 15,000 new African farmers grew tea in 1965. It was through his efforts that Kenya became a leading tea exporter.

By 1967, some 75,000 landless African families had been put on one million acres in the so-called White Highlands at $77 million (Kshs6.16 billion at the 2012 exchange rate). Britain, West Germany, the World Bank and the Commonwealth Development Corporation financed the programme. In the same year, McKenzie married Alice Christina Bridgeman, the daughter of Lt-Col Henry George Orlando Bridgeman, a British oil executive. Attorney-General Charles Njonjo was the best man at the wedding. Two years after marriage and the birth of their daughter Kim in May, 1969, McKenzie resigned from politics and quit as Minister for Agriculture. Jeremiah Nyagah replaced him.

Partly, McKenzie felt frustrated that the land settlement scheme did not pick up as expected and there was little manpower and extension services to cater for the new farmers scattered across the former White Highlands.

McKenzie has always been regarded as part of the British spy agents planted on the Kenyatta government to influence politics and policy at a crucial transition period. In private life, McKenzie doubled as an intelligence officer and is regarded as instrumental inKenya’s complicity in Israel’s raid on Uganda’s Entebbe Airport to rescue Israelis whose plane had been hijacked by Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO) agents in 1976 and flown to Entebbe.

He was also a large-scale farmer and owned huge tracts of land. His trademark company was DCK Kenya Ltd. McKenzie was also the chairman of Cooper Motor Corporation (CMC). With Keith Savage, he also had interests in Wilken’s Telecommunications Company. They owned Wilken Air, which was sold to CMC.

McKenzie died in the search for a business contract in Uganda in 1978. He had flown to Uganda to clinch the deal with Uganda’s President Idi Amin, whose handlers distrusted McKenzie, fearing that he could get close to the President. On their way back, an Amin ally put on board a lion’s head carving, ostensibly a gift from the President. It turned out to be a bomb that blew McKenzie’s Piper Aztec 23 aircraft over Ngong Hills as it prepared to land at Nairobi’s Wilson Airport. He was 59.