Kosgey was a loyal aide to President Daniel arap Moi, evident in the six Cabinet positions (including Transport and Communications, Culture and Social Services, Education, and Cooperative Development) he served in the Kenya African National Union (KANU) government between 1979 and 2002. “I was a good student of Moi and loyal to the government … Without him, I would not have ventured into active politics,” Kosgey said in March 2020 in an interview with the Daily Nation. And according to Wikileaks Cables, “although (Kosgey) is a member of the Nandi sub-tribe and not (former President Daniel arap) Moi’s Tugen sub-tribe, he was for many years a close and trusted associate of the former president.”

Understandably, Kosgey chose to stick with the Orange Democratic Movement (ODM) leader Raila Odinga although after 2008, the political ground in his Kalenjin land had shifted towards William Ruto, who had fallen out with ODM leader.

Yet it is instructive to note that this loyalty has never taken away his ultimate survival instinct. He’s loyal, yes. But he is also a politician deft at reading the signs of the time, as it were. Once KANU was defeated at the elections in December 2002, Kosgey ditched his cradle political party and opted for the nascent ODM at a time his mentor, Moi, was supporting his successor Kibaki.

Kosgey, like Kibaki, is composed and carries a gentleman’s mien; and both are steely inside, so to speak. Kosgey isn’t the swashbuckler of Kenya politics, but he is felt everywhere and those aspiring for political posts often scramble to seek his blessing or support — or even to be just seen as friendly with him. Just like Kibaki, Kosgey became a Member of Parliament (MP) at a nascent age of 32. Both quit their jobs — Kibaki from Uganda’s Makerere University and Kosgey from Kenya Breweries Limited — to plunge into the murky world of politics. And both endured for a long time in politics, and are now listed among Kenya’s longest-serving MPs (Kibaki 50 years; Kosgey 29 years).

Kosgey is among a handful of politicians privileged to have served both in the Moi and the Kibaki governments as Cabinet Ministers. Others include Odinga, Musalia Mudavadi, Kalonzo Musyoka, Simeon Nyachae, William ole Ntimama and Dalmas Otieno.

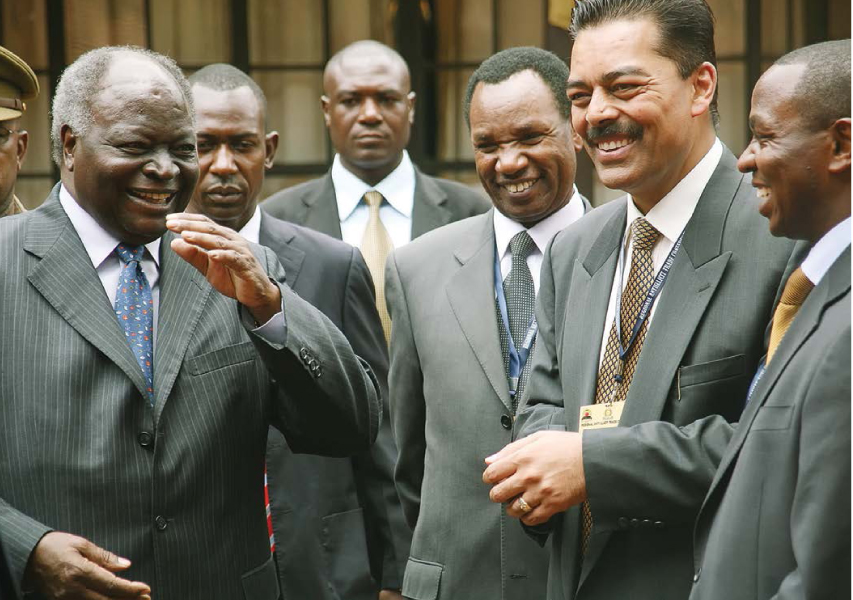

He is among the Opposition leaders who came out strongly to support the healing of the country even as the embers of the 2007–2008 post-election violence simmered. He was quick to mobilise in March 2008 the ODM party’s 107 MPs to endorse the handshake between Kibaki and Odinga. The Daily Nation captured this when it stated in May 2008: “the minister (Kosgey) called on Kenyans to forget the events of early this year and coexist as brothers and sisters”.

At the time, Kenya was heavily polarised following the divisive December 2007 General Election. But Kosgey chose to remain middle-of-the-road although he was in a camp clearly opposed to Kibaki’s win. Indeed, his respect for a person he once worked together in the Moi Cabinet was apparent. And Kibaki had a fondness for Henry Kosgey and wanted to have him in the Cabinet. So much so that in September 2006 the Head of State sent emissaries to Kosgey (then serving as KANU vice-chair) to convince him to join the National Rainbow Coalition (NARC) government. Kosgey turned down the offer.

“Having previously served in various ministries for over 15 years, I challenged them (emissaries) to state the specific ministry (President) Kibaki had assigned me. Of course they had no answer,” he confided in a September 2006 interview with the Sunday Nation. “I turned down the Cabinet offer because it was selfish and the wrong thing to do. I challenged the emissaries to instead negotiate through ODM or Uhuru (the then KANU chairman).”

The newspaper reported, thus: “the truth is that Kosgey and President Kibaki have come a long way and it is not surprising that he was targeted. He is in relatively good books with the past (retired President Moi) and present (Kibaki) leadership of this country. Apart from Kibaki with whom he worked closely and suffered in the infamous 1988 mlolongo (queue) voting system (Kibaki was dropped as VP), the MP coincidentally served as Minister for Education (1999–2002) with the Vice-President, Mr Moody Awori, as his deputy.” (Note that Moody Awori was Kibaki’s Vice President in 2006.)

And at times, despite the cordial relations, they sometimes disagreed — as happened in March 2007 just when Kenya was preparing for the General Election. Kosgey, as ODM-Kenya interim chairman, was among the first Opposition leaders to ask for calm and welcomed President Kibaki’s acceptance of minimum Constitution reforms. But he did this with the rider, reported in the Daily Nation: “We hope he is genuine and not hoodwinking Kenyans as he has done in the past.”

KANU’s defeat nearly ended Kosgey’s political life. But the 2005 change-the-Constitution moment gave him a lifeline; he joined forces with those opposed to a draft prepared by the Kibaki government. This camp, known as ‘Orange’ (the electoral symbol of those opposed the draft), included Uhuru Kenyatta, Odinga, Ruto, Musyoka, Mudavad, and Najib Balala. This camp defeated the draft in the ensuing referendum, and formed the ODM lobby that later became a political party, ODM-Kenya.

Kosgey became the ODM-Kenya interim chair. This gave him a lifeline, resulting in his re-election as Tinderet Constituency MP in the December 2007 elections on an ODM ticket after ODM-Kenya split following a disagreement between Odinga and Musyoka.

Given his top position within the party, he was in April 2008 appointed Minister for Industrialisation in the expanded 40-member Cabinet. His Assistant Minister was Ndiritu Muriithi. He oversaw the implementation of Vision 2030 (Kibaki’s signature legacy development plan) and the importation and manufacture of quality products. He was in charge of 10 parastatals under the Ministry.

Ideally, as the Minister of Industrialisation, Kosgey was in charge of the formulation, coordination and implementation of the national industrialisation policies and industrial property rights, provision of an enabling environment for domestic and foreign direct investment, promotion of the development of industrial tooling and machining, industrial research and development, innovation and technology transfer, and the initiation and promotion of industrial programmes and projects, among others.

David Nalo was the Permanent Secretary (PS) and was succeeded by Kibicho Karanja. Notably, the Ministry of Industrialisation was hived off from the Ministry of Trade and Industrialisation which had been led Mukhisa Kituyi. Kenyatta became Minister for Trade.

In 2009 Kosgey attempted to ban the importation of auto-spare parts after the Kenya Bureau of Standards (KEBS) argued that used vehicle parts were the cause of the many road accidents recorded at the time. Although the move was supported by the Kenya Motor Industry Association which described it as “political courage and technical good sense” in an interview with the Sunday Nation, a section of influential car dealers strongly opposed it. Since then, there have been various attempts to outlaw the importation but all have come to nought.

That apart, he was central to the establishment of the Anti-Counterfeiting Agency.

But more important, Kosgey superintended the initial implementation of Vision 2030, one of Kibaki’s major economic pillars that continue to define Kenya’s road to industrialisation. He was also the architect of the Memorandum of Understanding between the Kenya Industrial Estates (KIE) and the National Small Industries Corporation of India, to assist local entrepreneurs benefit from business incubation, technology transfer, marketing and training.

He encouraged manufacturers to take advantage of the international market by embracing unique packaging. “Kenya has merely scratched the surface in international trade. We need to move to the next level by branding Kenyan products using packaging as a key differentiator … We are not able to differentiate our products from South African or Egyptian based companies because we are in a comfort zone,” Kosgey said in an interview with the Daily Nation in November 2008.

However, during his tenure as Minister, his performance wasn’t extraordinary, perhaps because party matters took up the best of his time and effort. In October 2009 he was summoned by the Parliamentary Committee on Implementation for failing to achieve on his Ministry’s goals. And in February 2008 he was interrogated over a scandal (irregular sale of subsidised maize) that also implicated fellow Cabinet colleagues, Ruto and Naomi Shaban (Special Projects) and some 19 MPs.

Three years later, he was dropped from the Cabinet over accusations of facilitating the importation of cars whose age was over the limit set by the government. However, the President reinstated him seven months later after he was cleared of the charge.

Yet it is instructive to note that Kosgey, during the tail-end of his tenure as Minister had frosty relations with Assistant Minister Muriithi, PS Kibicho and some parastatal heads. The toxic atmosphere in the Ministry was evident in October 2010 when Kosgey’s appointment of Joseph Kipketer Koskey as the chief executive of KEBS was opposed by Murithi, the PS, and the National Standards Council.

As it were, Kosgey has been there, seen it all. He’s been accused of corruption, even hauled to the world’s top criminal court. Yet he has never been convicted.

Indeed, his accusers have failed to account for their claims, and 41 years since he joined Parliament, he is yet to be convicted of the myriad corruption allegations often arrayed against him — in particular that he embezzled funds earmarked for the 1987 All African Games, and that he superintended over the collapse of the Kenya National Assurance Company.

Wikileaks, for instance, claims Kosgey defrauded the government, grabbed public land, was involved in post-election violence, and lacked transparency in exercise of his job as Cabinet Minister.

In 2008, American authorities sought to declare Kosgey persona non grata. The US Ambassador to Kenya at the time, Michael Ranneberger, wrote to Washington, thus: “there is strong evidence that Kosgey has consistently engaged in official corruption from at least 1987 to the present while holding a variety of ministerial and parastatal director positions, and that corruption has had serious adverse effects on both U.S. foreign assistance goals and on the stability of Kenya’s democratic institutions,” according to Wikileaks.

He was in January 2011 forced to resign as Industrialisation Minister following accusations of abuse of office — that he facilitated the importation of hundreds of cars that were older than the statutory limit of eight years. “I wish to state that my actions in this matter are above reproach. I have committed no wrongs,” he told a press conference. However, the accusations fell flat and he was reinstated to the Cabinet in August 2012.

Kenyans recall the image of Kosgey in the dock at the International Criminal Court (ICC) based at The Hague, the Netherlands, answering charges of crimes against humanity following the post-elections violence of 2007–2008. The ICC Prosecutor Luis Moreno Ocampo had described Kosgey as a “principal planner and organiser” of violence against supporters of the Party of National Unity, as reported by Al Jazeera.

The charges were dropped. However, the arraignment in the global court marked Kosgey’s lowest moment in his political life. In an interview with the Daily Nation after ICC cleared him of the charges he stated: “facing crimes against humanity charges is traumatising. It does not take a weak man to go through. I will not wish anybody to go through that experience.”

Kosgey is very resilient — easily responding to the politics of the time and discarding any tag that risks holding him accountable for past misdeeds. In essence, he’s a survivor in his own right.

For instance, even after serving as KANU vice chair and a Cabinet Minister in the KANU government, he would later in July 2007 label the party as “an empty shell of a bee hive”, according to the Sunday Nation. And when Kibaki’s NARC party defeated KANU in the December 2002 General Election and Moi relinquished its leadership, Kosgey and Nicholas Biwott (a powerbroker during the KANU regime) fought over control of KANU in 2004–2005.

Although he had been a key cog in Moi’s administration, Kosgey immediately made an apparent about-turn during the reign of Kibaki. At one time in February 2007, he clashed with the then KANU factional leader Nicholas Biwott, who was always Moi’s right-hand man. “Biwott, why are you reducing the Kalenjin community to the culture of hand-outs instead of empowering them economically? This must stop, and let the community chart its own political destiny,” Kosgey told Biwott Iten.

Kosgey’s leadership role in ODM was essentially to make it a national party. He ensured that almost every part of the country was represented in ODM’s top leadership. He was very influential in moulding ODM to be as we know it today, always at the centre of the party’s move to counter any policies and laws deemed repressive and oppressive.

In another survival tactic, Kosgey was a key player in the implosion of the ODM-Kenya, in 2007. Despite being the interim chairperson, he sided with Odinga who was battling Musyoka for the party..

Notably, Kosgey has been a key figure in Rift Valley region politics, along with Ntimama, George Saitoti and Ruto. Kosgey has fought and won many battles in his 30 years in Parliament. In fact, if he had not lost his seat during the 1988 General Election, he would have been an MP for 34 unbroken years, equivalent to 7 electoral cycles. But now, how he reinvents himself after twice failing to win an electoral seat — Senator in 2013 and Governor in 2017 — is anybody’s guess.