In the rough and tumble of Nairobi City politics, Maina Kamanda was to Mwai Kibaki what Fred Fidelis Gumo was to Daniel arap Moi. A streetwise mobiliser, Kamanda stormed the political scene through his election as councilor for Ngara in 1979 aged only 28. He was for many years Kibaki’s commander in Nairobi City, rallying his troops of supporters on short notice, and mobilising resources to fund the third president’s politics for years.

Kamanda and Gumo — KANU’s one-time sole MP in Nairobi’s days as the opposition hotbed — were the city’s most memorable muscle men. Their wishes nearly always prevailed, often by brawn, with Gumo striking a blow for Moi and Kamanda ardently defending Mwai. Yet, for a man who dropped out of class seven to help his mother take care of the family—his father having died when he was only one—Kamanda’s rise from a settler’s goatherd on the slopes of the Aberdares to one of the most transformative cabinet ministers in Kenya is no mean feat. “I am the real hustler. I went through hell before I became a councilor. I couldn’t afford uniform, let alone fees for secondary school,” says the teetotaler whose politics at the peak of his career is hard to associate with the humble 70-year-old man at the time of our interview.

Kamanda loved politics from an early age, and mingled with politicians who patronised the hotels he worked in in his youth. “I accepted to join Wachira Waweru, then MP for Westlands, in 1976 as his personal assistant, a position which honed my skills even further.” Kamanda says he became popular, especially around the Ngara area, the reason he decided to run for the councilor’s seat in the 1979 General Election – and won. His decision to run was not received well by his boss, who refused to pay him his four-month salary arrears then totaling Ksh600, which would have gone a long way in securing the KANU life membership card he needed to run. The all-important card went for Ksh1000, a tidy sum at the time. “I had a very hard time raising the money. It was at this point that I went to a rich neighbour back in Murang’a who gave me Ksh3000, after trying in vain to laugh off what he thought was clearly a misguided mission.”

But his troubles were only starting as goons soon descended on him with pangas, leaving him for the dead. He won the election from his hospital bed. “Knowing that I worked for the MP, good Samaritans took me to the high-end MP Shah, instead of Kenyatta National Hospital where I truly belonged. As fate would have it, fellow councilors fighting for the prestigious mayoral seat vied to pay my hospital bills which had reached the prohibitive Ksh3000.” And so, with a brutal attack that nearly took his life, Maina Kamanda of Kiria-ini, Mathioya region of Murang’a, whose family moved to Nyandarua in his childhood, was initiated into Nairobi politics. The attack, for which he has bruises to date, combined with his difficult childhood to toughen the man into one of the most hard-nosed politicians of his time.

Kamanda’s first term at City Hall, however, was short as President Moi soon after dissolved the council prematurely, in 1983, after differences with Mayor Nathan Kahara. Kamanda then unsuccessfully contested for Member of Parliament (MP) for Parklands Constituency, in the subsequent election. He then retreated to his more familiar territory of City Hall politics until 1997 when he successfully contested for the Starehe Constituency parliamentary seat, which he retained in 2002. “As a young person I could picture a progressive Kenya under Kibaki. That is why

my like-minded colleagues and I approached Matiba and requested him that even though we all traced our origins to Murang’a he should allow us to support Kibaki,” he said in an interview with the Kenya Yearbook Editorial Board.

While his go-getter streak can be seen in his checkered political life, Kamanda’s confidence and never-say-die spirit reveals itself even more in his relentless pursuit of education.

Around 2000, Kamanda figured that if he had achieved so much without an education, he would surely do a lot more if he went back to school. He then enrolled for a General Certificate of Education (GCE) and studied by correspondence, graduating in July 2002. He earned another a certificate in County Governance from the Jomo

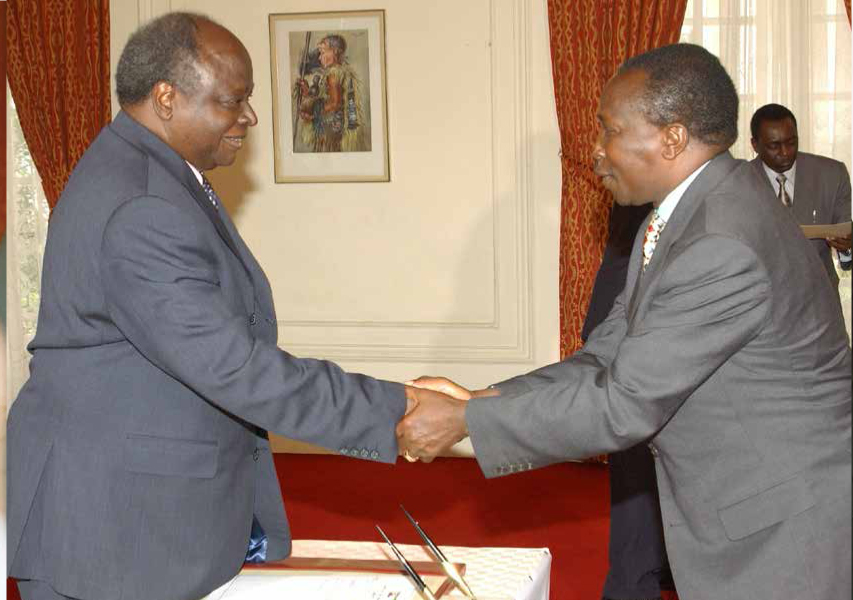

Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology in 2012, and a Higher National Diploma from Stratford Business School in the UK in 2016. He graduated in May 2021 with a degree in Business Administration from the Swiss Management Centre University, more than half a century since he left Kagaa Primary School. Kamanda believes that his GCE (an equivalent of Form Four qualification) went a long way in helping him deliver at the Ministry of Gender, Sports, Culture and Social Services. President Mwai Kibaki appointed Maina Kamanda to the Cabinet in 2005 in

a move aimed at purging the government of ministers who campaigned against the government-backed Constitutional Referendum earlier that year.

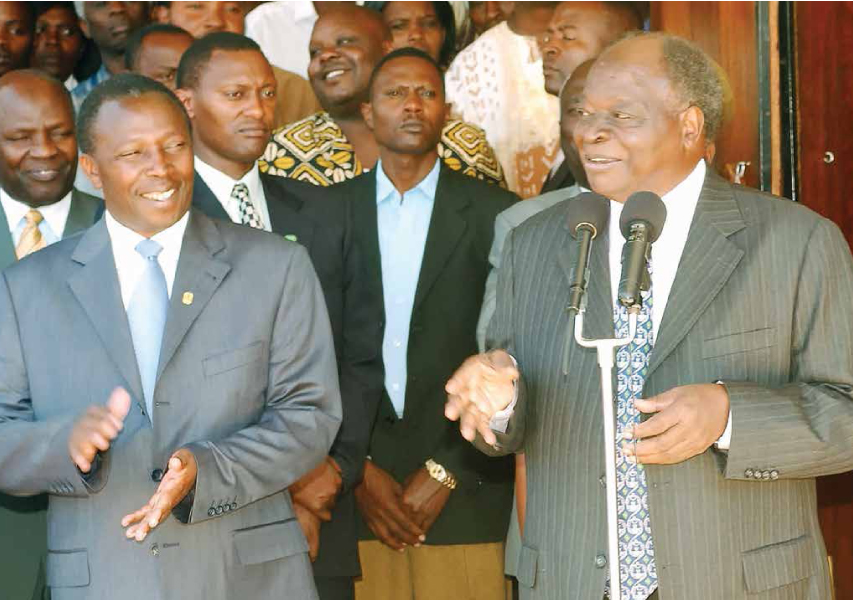

Referring to Kibaki as a miracle for Kenya, Kamanda says that the third president was a brilliant tactician who, even before he became president, never spoke ill of Moi in the hearing of anyone. This, Kamanda believes, helped to preserve the future president for Kenya’s transformation. Analysts believe that Kibaki appointed Kamanda, a former long-serving Nairobi councilor to the Cabinet to help him manage the fluid city politics. “Kibaki could not hold a Nairobi meeting without consulting me. Anytime I called a small fundraising in Nairobi I would raise millions within no time, more than any other branch. I had seen the man who would save Kenya. I often wonder how Kenya would have been if he came to power earlier, say, from 1992,” Kamanda says in his forthcoming biography.

Alongside the then Kamukunji MP, Norman Nyagah, who became Parliamentary Chief Whip, Kamanda was one of Kibaki’s most passionate loyalists, shooting from the hip and firing with abandon at any real or perceived nemeses. Between 1988 and 1992, he was Secretary of KANU’s Nairobi branch, before becoming Nairobi chairman of Kibaki’s Democratic Party (DP) in 1992 at a time when Matiba’s Ford Asili was sweeping Nairobi through to 2013 when it merged with other parties to form Jubilee.

In the heady days when it was not clear whether President Daniel arap Moi would cede the reins of power if his political protégé, Uhuru Kenyatta, was trounced in the 2002 General Election, Kamanda was arrested on allegations of treason, becoming the first person to be so accused since the country transitioned to multipartism in 1991. Kamanda was placed in remand prison in Embu District (today’s Embu County) for remarks he allegedly made at a public rally at Kinoru Stadium in Meru District. Reportedly, Kamanda had said that President Moi should be shot if he vied for another presidential term.

As he awaited trial, Kamanda, in his own words, said he had entrusted his fate to God owing to the severity of the charge that could potentially lead to death by hanging. Members of the Central Kenya Parliamentary Group, the organisers of the public rally attended by more than 30 legislators and where Kamanda was alleged to have made the statement in 2001, spoke up for him, calling for his speedy release with an unequivocal message that they were “fed up with continued harassment, threats, and intimidation by the police, the courts and the provincial administration on instructions by the Moi government.” The Church, on its side, struck a conciliatory tone, saying forgiveness was crucial to the country’s continuity. The Reverend Mutava Musyimi, then of the National Council of Churches of Kenya (NCCK), memorably stated that there is no justice so severe that it cannot be tempered by mercy. So, how did Kamanda disentangle himself from a yarn that threatened to spiral all the way to the hangman’s noose? His lawyers, Paul Muite and James Orengo, dispelled the charge and accused the national broadcaster, Kenya Broadcasting Corporation (KBC), of distorting Kamanda’s speech “so as to deliberately implicate him in an imaginary treason charge.”

The two lawyers later announced that Amos Wako, who was then the Attorney General, had agreed to evaluate the validity of the treason charge after he was presented with alternative footage. The treason charge was later dropped and Kamanda freed on bail but charged with incitement to violence. As supporters of the Democratic Party danced in the streets after the treason charge was dropped, Kamanda’s credentials soared. He affirmed his standing as a stalwart that Kibaki could rely on as he tried to oust Moi from power. Already, Kamanda was one of Kibaki’s chief strategists in Nairobi, a cosmopolitan hub whose eight constituencies had fallen under the opposition spell in the 1997 elections, when Moi’s KANU won a single seat (Gumo’s Westlands). Kibaki’s DP swept five of the seven seats aligned to the opposition.

To date, Kamanda fervently denies the Moi-should-be-shot remarks. “My statement was twisted by KBC and even Moi was later embarrassed by the charges when he learnt the truth. What I said was that Moi had outlived his stay in

power. Norman Nyagah worked hard to produce the original video that vindicated me.” As MP for Starehe, which then comprised Nairobi’s Central Business District, City Square, Ziwani, River Road, Kariokor/Starehe and Pangani sub-locations of Ngara Location, and Huruma and Mathare locations, Kamanda had the advantage to being able to keep his finger on the political pulse of the capital city. After the watershed 2002 General Elections, Kamanda served as Assistant Minister in for Local Government from 2004 to 2005, and as Minister for Gender, Sports, Culture and Social Services between 2005 and 2007.

President Kibaki’s first-term government was riddled with internal squabbles due to accusations of betrayal by allies of Raila Odinga, whose endorsement – the ‘Kibaki Tosha’ proclamation – and extensive nation-wide campaigning – helped to galvanise the country around Kibaki. Kamanda proved himself adept at playing the role of a dependable slugger as he leveraged his position to make sensational allegations against the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), which was allied to Odinga.

In Parliament, he alleged that the LDP wing of the coalition was defeating key government-sponsored Bills using illicit monies sourced from the Goldenberg scandal (1991 to 1993), which remains the largest known fraud ever committed against the exchequer, to influence voting patterns in the House with the intention of upending

the Kibaki administration. Kamanda also helped fan differences during the Bomas of Kenya Conference, leading to the discarding of the Yash Pal Ghai Commission-proposed constitution draft. He was one the hardliners during the squabbles over an alleged Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between Kibaki and Odinga to appoint the latter as Prime Minister. Kibaki never made the appointment, which led to a troubled first term as President due to endless squabbles in his fractured government. Kamanda was also one of the key supporters of the Kilifi Draft on the proposed constitution, which was later defeated in the 2005 referendum, leading to the dismissal of rebel ministers.

Yet it was not all rabble-rousing for Kamanda. An excellent performer as a minister, he initiated many reforms that remain to date in the Sports docket. “If you go to that ministry today, they will tell you nobody ever matched what I did there,” he proudly says.

He helped recover Kasarani Moi Sports Complex land, which had been grabbed. “Sixty acres had been grabbed and I appealed to people who had ‘bought’ the land to return their title deeds. I took the titles to the Ministry of Lands for them to be cancelled. Some even had built houses, but they still returned their titles. I then fenced off the whole area.”

He also he promoted the speaking of Kiswahili locally and internationally, pushing for official speeches to be delivered in the national language. The politician, who was deputised by Alicen Chelaite and Joel Onyancha, with Rachel Dzombo as their Permanent Secretary, says Kibaki never micro-managed or interfered with ministers’ work. This was unlike the Moi era when “they could be summoned even by chiefs.” He recalls a time when Kibaki asked him who he wanted appointed to some parastatal and he asked: “are you short of people in Kenya?” Former Commissioner of Sports Gordon Oluoch reckons that Kamanda’s strongest point was the fact that he let the technical team run the affairs of sports and only guided even as he motivated staff.

“When the government introduced performance contracting, Sports was rated number one and all the staff were given salary bonuses,” says Oluoch, adding that Kamanda came in when Kenya’s football was in turmoil, and he went about fixing it. “He brought the world governing body, FIFA, twice and went to them twice – in Cairo and Zurich.”

Kamanda grabbed international headlines for disbanding the Kenya Football Federation (KFF), the governing body of football in Kenya. This provoked FIFA to temporarily suspend Kenya from international competitions. Kamanda had taken the drastic action because KFF was beset with warring factions that seemed hell-bent on disrupting the running of football in the country. Oluoch lists Kamanda’s other achievements as successfully hosting the World Cross Country Championships in 2007 in Mombasa, only the second such fete in Africa, and a successful Commonwealth Games in Melbourne, Australia.

“He also standardised the awards system which had been sporadic and subjective. To date, the figures have been adopted by the Salaries and Remuneration Commission,” Oluoch says and adds that Kamanda brought all units of sports together, meeting almost every week to plan activities. According to Oluoch, Kamanda’s strongest point is that he acknowledged his deficiencies on matters sports and relied on experts whom he found in the ministry. Away from sports, Kamanda will also be remembered for chairing the National Assembly’s Committee on Transport, Public Works and Housing that cleared the way for building the standard gauge railway project, the single largest infrastructure project in Kenya.

The government should proceed with the process of implementing the Mombasa-Nairobi Standard Gauge Railway project due to the immense benefits that will accrue to the people of Kenya

In February 2014 he told the House: “The government should proceed with the process of implementing the Mombasa-Nairobi Standard Gauge Railway project due to the immense benefits that will accrue to the people of Kenya during the construction period and upon completion of the project.”

In 2007, Kamanda was trounced in the race for the Starehe seat by Bishop Margaret Wanjiru, who rode the ODM wave associated with Odinga. But Kamanda would later redouble his efforts and chart a path back to Parliament in 2013. Those who were quick to write his political obituary after a defeat in the Jubilee Party nominations for Starehe recoiled when Kamanda made a comeback as a nominated MP in 2017. Away from politics, the proud polygamist of two wives today divides his time between his Runda and Muthaiga homes in Nairobi, as well as his rural Ol Kalou and Mathioya turfs.

In appointing Kamanda, a humbly educated, yet hard-nosed city operative to the Cabinet, Kibaki struck two feats: he stabilised the government at a time of much squabbling, while tapping into the leadership qualities of a man who, though underrated and dismissed as an illiterate rubble-rouser, ended up being the best-rated minister in the first-ever performance contracting introduced in 2007 to improve service delivery.