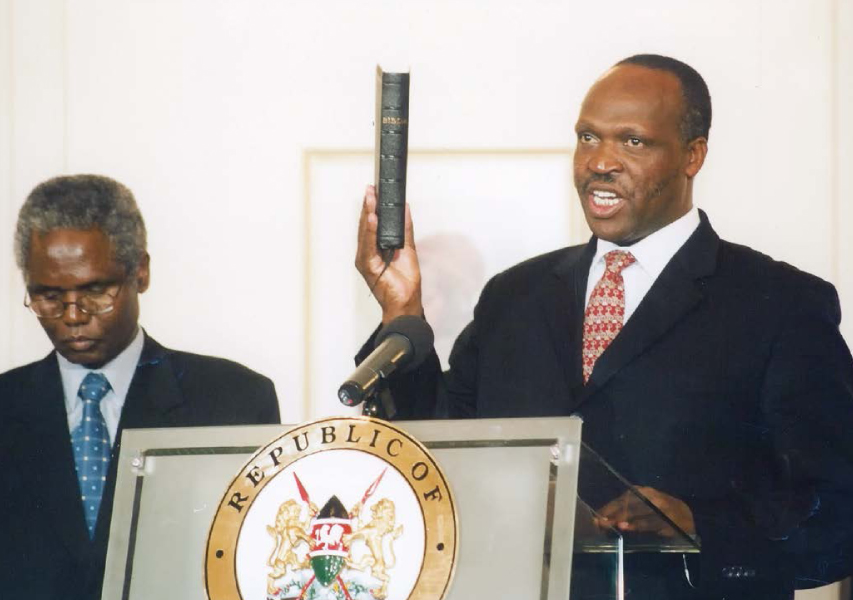

Kipkalya Kiprono Kones was part of President Mwai Kibaki’s Cabinet for just 57 days before his death in a plane crash on 10 June 2008, aged 56. Given such a brief stint, it is difficult to put a finger on any agenda he might have had that would have contributed to the legacy of Kenya’s third President. However, a review of the Hansard (Parliament’s record of proceedings) of June 11, a day after his death, presents a peek into this politician who went about everything he laid his hands on with zeal and aplomb. Kones, a veteran politician who represented Bomet Constituency from 1988 to 2008 with only one hiatus – from 2002 to 2007 (and even then he was a nominated MP) –found his way into the Cabinet through the power-sharing pact that saw Kibaki and Raila Odinga form the Government of National Unity. The pact was the result of protracted negotiations to quell violent unrest in the country after the disputed 2007 General Election. President Kibaki announced a coalition government comprising 40 ministers and 57 assistant ministers on 14 April 2008.

Kones was handed the influential Ministry of Roads and Public Works. This was familiar territory – he had once headed the Public Works and Housing docket under Kibaki’s predecessor, President Daniel arap Moi. While eulogising the fallen Minister, Odinga, who was Prime Minister in the coalition government, said he had had an opportunity to work with Kones very closely and found him dependable. “In recent times, before the dissolution of the Eighth Parliament, he had served briefly as my Assistant Minister in the then Ministry of Roads, Public Works and Housing. We worked very closely because he had been a Minister before in that ministry and he knew a lot of things. Together, we were able to carry out several reforms in the ministry,” Odinga said without going into detail.

He said after Kones was appointed Minister for Roads, he went to the PM’s office with his staff and explained his plans and vision for the ministry.

“He explained what he intended to do for this country. So the printed estimates that have just been laid on the table of the House include those for the Ministry of Roads. The estimates of the Ministry of Roads basically bear the thumbprint of Mr Kones,” explained Odinga while seconding a motion of adjournment to mourn Kones and Lorna Laboso, the MP for Sotik Constituency and an Assistant Minister in the Ministry of Home Affairs, who died in the same crash. One of Kones’ last official acts was to accompany President Kibaki to the Tokyo International Conference on African Development (TICAD IV) held in Yokohama, Japan, between 28 and 30 May 2008. At the event, Kibaki put up a spirited campaign for Kenya’s tourism sector, calling for direct flights between the two countries,according to press reports at the time.

Shortly after the Japan tour, Kones would also represent the President, with Odinga, at the World Economic Forum in South Africa where he made “a very positive contribution, leading to the Kenyan delegation being hailed as the most organised and prepared at that conference”, recalled the former PM. Jovial, yet strikingly fearless and warlike at the same time, Kones easily made friends from both sides of the political divide. And this was evident in the different politicians that eulogised him. For instance, describing his contributions in the House as being of the highest quality, Beth Mugo, then Dagoretti MP and Minister for Public Health, recalled a time when she invited Kones to her home, where he immediately struck up a friendship with her husband. Kones and Mugo, a staunch Kibaki supporter, were in opposing political camps that duelled bitterly in the 2007 election and in the months before the signing of the National Accord that restored peace in the country.

Sally Kosgei, the Minister for Higher Education and one-time Head of Civil Service in President Moi’s government, described Kones as a brilliant communicator with an infectious smile. “You would go to him because you thought the world was coming down, but his first response would be to laugh and you would realise that all was not lost.” Having schooled only up to Form Six in a region that produced the likes of Prof Jonathan Ng’eno and Dr Taita Towett – Cabinet ministers in years gone by – Kones was not considered well-educated in his larger Bomet-Kericho backyard, but his eloquence and mobilisation skills were widely acknowledged. This, combined with his courage, is what endeared him to Moi, who kept him on as Minister for nearly 15 years.

Kones attended Tenwek High School from Form One to Form Four and then Cardinal Otunga High School for his A’ levels after which he was employed as a supervisor at James Finlay Tea Company in Kericho District (now Kericho County). It was here where the beautiful green expanse of tea stretches as far as the eye can see – that the young Kones fell in love with politics, riding on his oratorical skills and a knack forspeaking his mind. His attempt to become the Bomet MP in 1983 was, however, thwarted by the incumbent, Isaac Salat, then a powerful Assistant Minister in the Office of the President. Salat, a personal friend of Moi’s, was the father of the KANU (Kenya African National Union) party’s Secretary General, Nick Salat.

The elder Salat’s death in 1988 yanked the door wide open for Kones, who was appointed Assistant Minister for Agriculture upon his election as MP. Ahead of Kenya’s return to pluralism in 1991, Kones teamed up with KANU

stalwarts William ole Ntimama, Nicholas Biwott and Henry Kosgey to try and mobilise Rift Valley residents to resist the idea. He would employ figures of speech to shape the course of events in the Rift Valley region so effectively that after the 1992 polls, during which he was re-elected as Bomet MP, Moi appointed him a Minister in the Office of the President.

In the 1997 elections, he was again re-elected and this time, appointed to head the Public Works and Housing docket, before being moved to Research, Science and Technology. Towards the 2002 General Election, however, his loyalty to KANU came under close scrutiny and he was moved to the less influential Ministry of Vocational Training.

Kones finally fell out with Moi altogether and briefly joined the Muungano wa Mageuzi movement, led by lawyer and fellow politician James Orengo, that was pushing for a regime change in the country. Kones’ sojourn in the Orengo camp was short-lived because shortly before the 2002 General Election, he shifted his support to FORD-People, which was led by Simeon Nyachae, a former Head of Civil Service and Cabinet Minister who had also fallen out with Moi. Nyachae, who had earlier parted ways with the National Rainbow Coalition (NARC) after Odinga endorsed Kibaki as the coalition’s presidential flag bearer, picked Kones as his running mate and the two put up a spirited fight for the presidency, flying around in helicopters during the campaigns, which was a novelty at the time. But they were no match for NARC’s Kibaki, Charity Ngilu and Kijana Wamalwa on the one hand, and a group of disgruntled ministers, led by Odinga, that had fled KANU on the other.

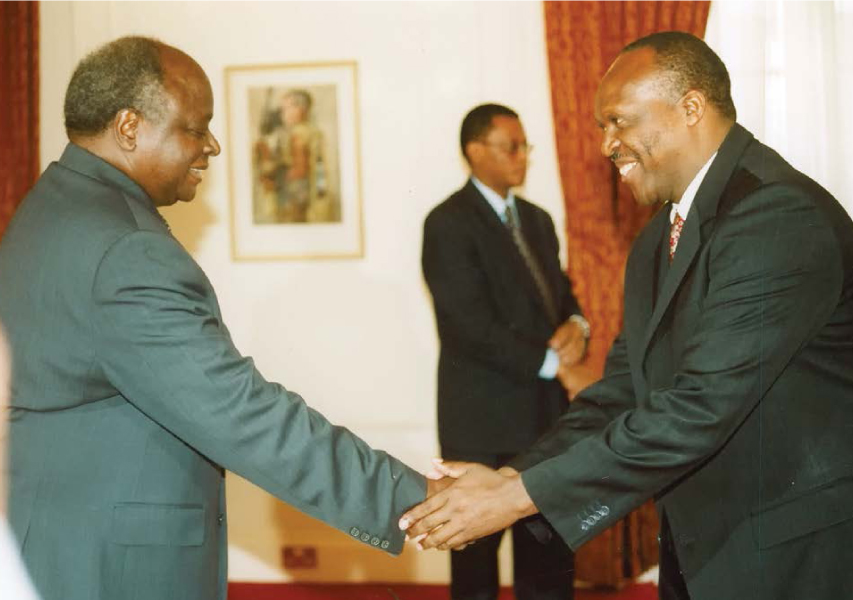

That year, Kones lost his parliamentary seat to Nick Salat but was nominated as an MP by the FORD-People party, which he also chaired. On 30 June 2004, Kibaki appointed Kones Assistant Minister for Public Works as he sought to beef up his support in Parliament following a rebellion from a number of ministers led by Odinga, who alleged an unfulfilled power-sharing pact. This was the first time Kones was working with Kibaki albeit from a distance since he

wasn’t a Cabinet member. At the time the full Minister from the Kipsigis community was Chepalungu MP John Koech, who was Kones’ nemesis in the jostling for the region’s numero uno position in politics. Koech had come into the Government of National Unity at the same time as Kones. In 2005, after the government-backed referendum to change the Constitution of Kenya failed and Kibaki purged his government of ‘rebels’, Kones refused an attempt

to reappoint him to his old job as Assistant Minister, reckoning that the ‘ground’ was hostile. He would later move to associate with Odinga, who had led the ‘No’ side of the referendum that was symbolised by an orange and that became the Orange Democratic Movement (ODM) party on which Kones rode to Parliament and into the Cabinet after the formation of the coalition government.

Lawyer Gitobu Imanyara, then the MP for Imenti Central Constituency in Meru District, remembered Kones as a fighter who represented far more than his constituency or “even the larger Kericho (Kipsigis) region”. Imanyara recalled a time when he accompanied Kones to a fundraiser in his constituency and agents of the provincial administration attempted to stop them. The MP laughed loudly but stood his ground and said: “We are not moving. Go and tell Mr Moi that we are here to raise funds for a needy child.”

By invoking the needs of a poor child, he struck a chord even with the law-enforcing agents, who let him be. Appealing to the emotions was a tactic Kones had perfected over the years to pull even opponents over to his side. As a Minister of State in the Office of the President in the 1990s, his motorcade was once pelted with stones as he tried to get to a rally in Sotik through the neighbouring Chepalungu Constituency. He believed the hooligans that hurled stones at him had been hired by Chepalungu MP Isaac Ruto, a contender for supremacy in the region. “If a whole Minister in the Office of the President can be stoned in broad daylight, then what is the security of these ordinary people here? Indeed, what’s the security of these old women?” Kones emotionally asked the crowd at Ndanai in Sotik

Constituency. The next day the Daily Nation ran the story on page one with the headline: ‘Kones weeps’.

Throughout his political career, Kones was known for making populist remarks delivered with dramatic flair for effect. One of his campaigns of infamy was his opposition to a government drive to entrench family planning in communities. He wanted the so-called small ethnic communities to get more, not fewer, children so they could catch up with the larger communities in the number of votes – for the political gain of patrons such as himself. This was, however, couched in the clever, more polite explanation that more people in the region would equal a bigger share of the national cake. In his opposition he found good company in Ntimama from neighbouring Narok District. For their war-mongering, they were both mentioned adversely in commissions of inquiry that were formed following deadly tribal clashes in the Rift Valley region.

Kones was one of the 21 politicians and famous personalities named in a Kenya National Human Rights Commission report for allegedly planning and financing the 2007-2008 post-election violence that led to the deaths of more than 1,000 people and displacement of more than 500,000 others. He had earlier been implicated in a report by a Parliamentary Select Committee chaired by Changamwe MP Kennedy Kiliku on ethnic clashes that rocked parts of the former Rift Valley and Western provinces. The Judicial Commission of Inquiry into Tribal Clashes (1991/1992) headed by Justice Akilano Akiwumi also fingered him as one of the perpetrators. His intransigence also came to the fore when he opposed the eviction of thousands of settlers from the Mau Forest, telling them to stay put because they had purchased the parcels of land on which they lived.

“You don’t have anywhere to go to. From here, you will go to heaven. Back to your Maker, God,” he said ahead of the evictions by the NARC government in July 2005. He rode on these populist antics to reclaim his Bomet seat from Salat in 2007.

Kones’ wife, Beatrice Cherono, who became MP in the by-election following his death, credited her husband with building schools and other infrastructure besides helping many needy people gain access to education. Generous to a fault, Kones was a sociable person able to mingle with people from all walks of life – buying them food and drinks, and stopping only when he ran out of money. Whether out of this generosity, poor financial planning, political persecution or a combination of all these factors, the Minister fell on hard times at some point in the 1990s – to the point that he could hardly pay his own children’s school fees among other financial obligations.

In an interview in 2018, Kones’ widow reminisced about these hard times and alleged political persecution, saying the taxman was unleashed on the politician with fictitious arrears after he became a harsh government critic. “We had children to educate and rent to pay in Nairobi among other commitments, yet we had no money. Our friends and relatives assisted us,” she told the interviewer. Like Ntimama, his political friend from across the Maasai Mara game reserve, Kones was a voracious reader. His admirers said it was by reading that he was able to polish his oratorical skills, delivering choice epithets against critics and praise for his political idols when it suited him. Among the books he read regularly was The Prince by Nicolo Machiavelli from which he skimmed political cunning for which he was

well-known in Bomet. Ruto, his friend-turned-foe-turned-friend again in the political gymnastics of the Moi era, described him as a happy-go-lucky fellow who never kept grudges for long. And he should know – in clinching the Chepalungu seat in 1997, Ruto stood on Kones’ shoulders. The latter was happy to help cut down to size Koech, a formidable competitor in the political supremacy wars of the Kipsigis community.

Once in Parliament, however, Moi began pitting Ruto against Kones; after helping Ruto beat Koech, his Vocational Training ministerial job was taken away from him and handed to the same Ruto. After going their separate ways in the 2002 elections – Kones running on the FORD- People ticket and losing but getting nominated, and Ruto barking up the NARC horse and losing to KANU’s Koech, the two politicians made up, both fighting for their political survival via ODM in the 2007 election and triumphing. For Kones, that victory was short-lived as death came calling less than three months later.

Eulogising Kones, Kibaki said he had lost a hard-working public servant. “Kenya has lost leaders of immense potential at their prime age and with a promising future,” the President said of Kones and Laboso. In the final analysis, while Kones’ political skills and work ethic were widely acknowledged, his suspected involvement in the organisation and funding of ethnic strife in the restive Rift Valley was a blot on his otherwise sterling career. It would

appear that in naming him Minister, Kibaki was only following the diktat of the National Accord that gave Odinga, his main challenger in the 2007 election, a say in the Cabinet’s composition.